The Art of the Invisible: How One Scientist's Failed Experiment Captured the Hidden Beauty of Life

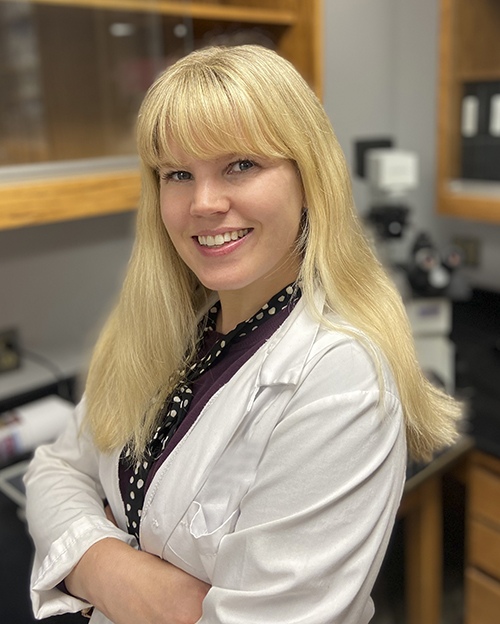

What if a botched stain could reveal a hidden world? That’s exactly what happened for Dr. Amy Engevik when a lab mishap unexpectedly produced a mesmerizing image of a mouse’s small intestine—so striking it placed her fourth in the 2024 Nikon Small World Competition. Renowned for spotlighting the world’s finest photomicrography, the contest recognized something truly special in this accidental discovery.

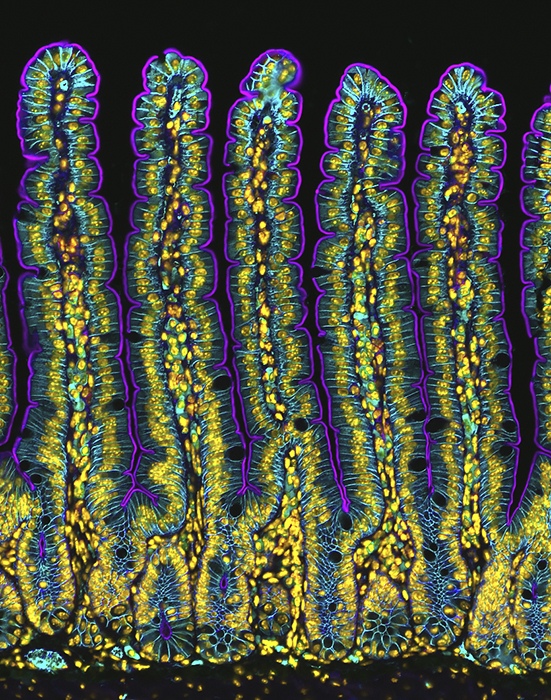

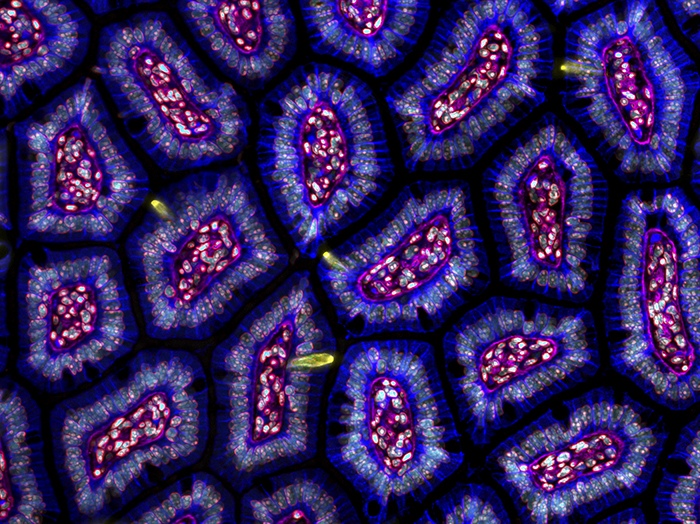

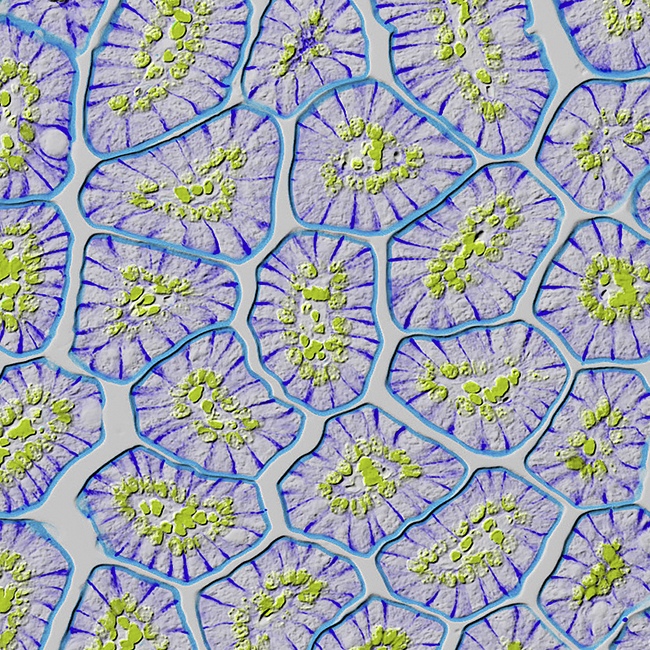

In vivid purples and teals, Dr. Engevik’s award-winning photo more closely resembles an abstract masterpiece than a scientific specimen. Under the microscope, perfectly aligned intestinal structures unfold like an otherworldly forest, reminding us that some of the most remarkable insights can arise when we least expect them.

When Failure Becomes Opportunity

“It was actually an unexpected outcome,” Dr. Engevik recalls with a laugh. “My primary stain had failed, but the secondary stains revealed something remarkable.” That something was an exceptionally rare view of intestinal villi—microscopic, finger-like projections that help our bodies absorb nutrients—arranged in perfect alignment.

As an Assistant Professor at the Medical University of South Carolina’s Department of Regenerative Medicine & Cell Biology, Dr. Engevik has dedicated her career to unraveling the mysteries of gastrointestinal health. Through thousands of microscopic images taken during her research, she’s documented the intricate cellular world that holds the keys to understanding disease and healing. While her work is scientifically rigorous, it often reveals unanticipated beauty—just as her Nikon-recognized photo demonstrates. Yet her journey to becoming a leading GI researcher wasn’t always straightforward.

From Family Legacy to Scientific Pioneer

Scientific pursuit runs deep in the Engevik family. With parents in medicine—her father a doctor and mother a nurse—and sisters who became accomplished scientists—one a microbiologist and current research collaborator, the other a virologist with whom she also collaborates—Engevik seemed destined for a career in science. However, it wasn’t until her doctoral studies at the University of Cincinnati that she discovered her true passion in an unexpected research area.

“I actually planned to study breast cancer,” she reveals. Instead, a mentor introduced her to the fascinating world of the gastrointestinal tract, where she discovered an elegant system of interconnected structures that would become her lifelong passion. Her early research focused on understanding how the stomach repairs injuries like ulcers, a pursuit that would eventually lead her to broader questions about how our bodies heal themselves.

Decoding the Image: A Microscopic Journey Through Intestinal Architecture

In her award-winning image, Dr. Engevik reveals just a glimpse of the intricate world she studies daily. What might appear as merely a pattern of purple and teal tells a profound story of life at the microscopic level. The purple-stained areas highlight the apical membrane of enterocytes, the most abundant cells in the small intestine, crucial for nutrient and water absorption. These cells are covered with microscopic projections called microvilli that dramatically increase the surface area for absorption, while specialized transporters within facilitate the movement of substances like sodium and glucose. The teal-colored regions show the basolateral membrane, which maintains essential cellular barriers against harmful bacteria.

Beneath these primary structures lie the nuclei of stromal cells, forming part of the intestine’s complex organizational framework. At the base are the crypts—cellular nurseries where stem cells emerge to populate the villi above, exemplifying nature’s efficient design in the constant process of renewal and regeneration. Perhaps most fascinating is what can’t be seen in the image: the glycocalyx, an invisible guardian that forms a critical protective barrier between microbes and the intestinal epithelium. This thin mucus layer plays a central role in host-microbe interactions, preventing direct contact between microbes and the epithelium that could trigger immune responses.

The importance of this system becomes clear when examining conditions where these processes are disrupted, such as when the protein myosin 5B becomes non-functional, leading to issues like diarrhea. Through this detailed cellular architecture, the image provides crucial insights into how these intricate relationships maintain both intestinal health and the delicate balance between host and microbiome.

Behind the Lens

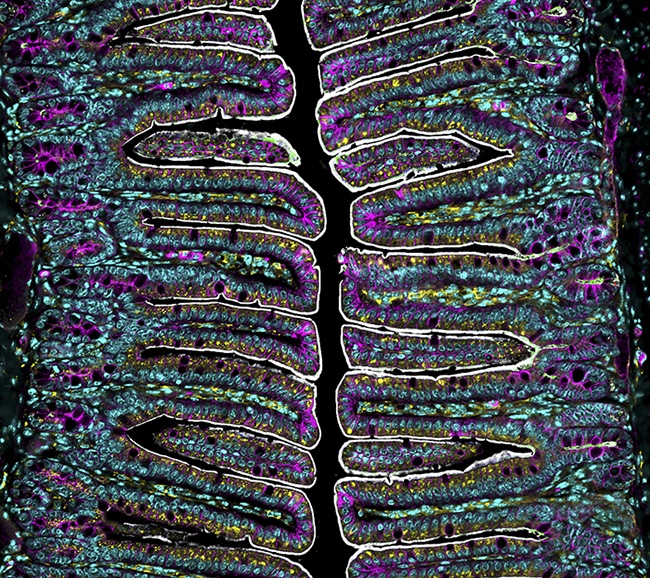

Creating these striking images is anything but simple. Dr. Engevik’s process is more akin to a master craftsman’s work than a simple point-and-shoot operation. Each image begins with a painstaking technique called Swiss rolls—a method that allows scientists to examine an entire intestine on a single slide, requiring the steady hands of a surgeon and the patience of a saint.

“The process is incredibly demanding,” Engevik explains. The tissue must be carefully embedded in paraffin wax, sliced into sections thinner than a human hair (just 4-5 microns), and delicately mounted on slides. Then comes the artistry: using antibodies like pigments on a palette, she stains specific cellular components to make them visible under the microscope.

For this particular image, Engevik chose a Zeiss Axio Imager—a widefield microscope that captures all available light rather than the single plane typical of confocal microscopes. “It’s about finding the right tool for the right job,” she notes. “Sometimes the most advanced technology isn’t always the best solution.”

The Art of Scientific Resilience

When asked what wisdom she’d share with aspiring researchers, Engevik’s response reveals the philosophical depth that underlies her scientific pursuit. “In science, resilience is your greatest ally,” she reflects. She points to the COVID-19 pandemic as a powerful example: researchers who spent decades studying coronaviruses, often struggling for funding and recognition, suddenly found their work crucial to humanity’s survival.

“Today’s overlooked research could become tomorrow’s salvation,” she says. “Keep your mind open and your curiosity sharp. Let the data be your guide, but never lose the capacity to be surprised.”

The Future of Discovery

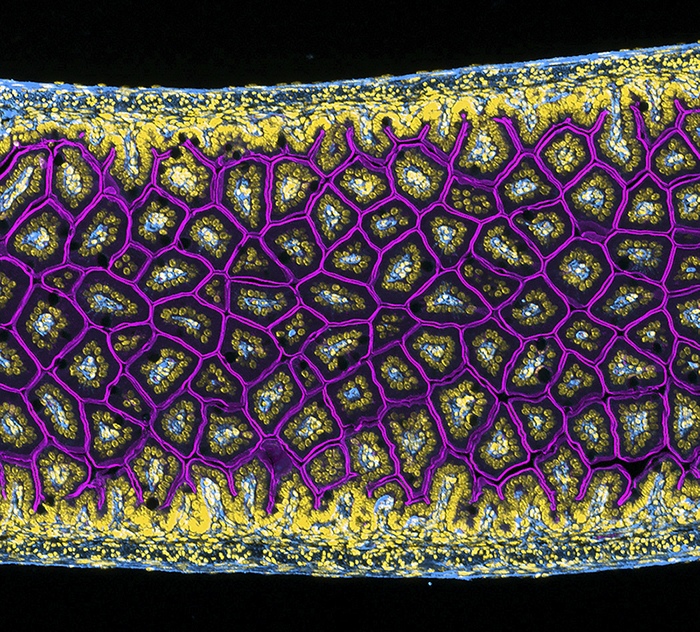

Modern microscopy has opened new frontiers in cellular research, with super-resolution imaging providing unprecedented detail of life’s smallest structures. Yet Engevik is quick to point out that technology is only part of the equation. “The real breakthroughs come from how we use these tools to understand the complex relationships between hosts and microbes in their natural context.”

Her work has particular relevance in studying how pathogens like H. pylori and C. difficile interact with our bodies, potentially leading to new therapeutic approaches for protecting gut health. It’s a perfect example of how visualization techniques can bridge different scientific disciplines, from microbiology to immunology, offering insights that might otherwise remain hidden from view.

Breaking New Ground: Current Research and Future Horizons

When asked about her upcoming projects, Engevik’s eyes light up with enthusiasm. Her lab is currently pursuing two groundbreaking research directions that could reshape our understanding of digestive health. The first tackles the growing challenge of inflammatory bowel disease, a condition affecting millions worldwide. The second—and perhaps more surprising—investigates how our modern diet, particularly high-fat foods, impacts the stomach’s function.

“The stomach is often the forgotten organ in GI research,” she explains, her passion evident. “But our findings suggest it’s a crucial player in overall health.” Her team has discovered that diets high in animal fats and processed foods may be disrupting fundamental processes in our stomachs, creating a cascade of effects throughout our bodies that reach far beyond simple digestive issues. Their research suggests connections to brain function, heart health, kidney performance, and even cognitive abilities. “It’s a perfect example of how everything in our body is connected,” she notes. “What we’re seeing is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Where Discovery Meets Beauty

As our conversation with Dr. Engevik draws to a close, it’s clear that her work represents something larger than just scientific research or microscopic photography. Her award-winning image—born from a “failed” experiment—reminds us that beauty and discovery often emerge from unexpected places. Through her lens, we glimpse a hidden world where art and science dance together, where the boundaries between creative expression and scientific inquiry blur into something greater than the sum of its parts.

As we face growing health challenges in our modern world, with changing lifestyles and diets impacting our bodies in ways we’re only beginning to understand, Dr. Engevik’s work shows us that sometimes the biggest breakthroughs come from looking at the smallest details. Her approach, combining rigorous scientific methodology with an artist’s eye for beauty, may just help us unlock new solutions to some of our most pressing health challenges.

“Science is about being open to surprise,” she reminds us. And perhaps that’s the most beautiful lesson of all—that in the intricate landscapes of our own bodies, there are still countless wonders waiting to be discovered, if only we know how to look for them.