Ancient Insights: Unveiling the Mysteries of Rock Art in the Colombian Amazon

In a groundbreaking study published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, archaeologists have uncovered a remarkable collection of ancient rock art deep within the Colombian Amazon. These ochre paintings, located at Cerro Azul in the Serranía de la Lindosa, date back as far as 12,500 years, offering an extraordinary glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and ecological knowledge of the region’s earliest inhabitants. Dr. Mark Robinson, an Associate Professor of Archaeology at the University of Exeter, has been at the forefront of this research, revealing the intricate relationships between these early settlers and the animals they encountered. In this interview, Dr. Robinson discusses the significance of these discoveries, the challenges faced in accessing such remote sites, and the profound insights the rock art provides into ancient Amazonian mythology.

Q: How long did you spend in the Amazon conducting this research?

A: My work in the Amazon, specifically in Colombia, began in 2018 as part of a significant project funded by the European Union. Led by my colleague Dr. Jose Iriarte from the University of Exeter, this project was initially planned as a five-year study. However, due to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the timeline has been extended. Over these years, we’ve closely collaborated with Colombian researchers, including Gaspar Morcote-Ríos and Javier Aceituno, to explore the rich archaeological sites, particularly the stunning rock art at Cerro Azul. Although my primary focus has now shifted to other projects in Belize, my experience in the Amazon has been unforgettable. The region’s incredible natural beauty and deep cultural history have left a lasting impact on me, offering new insights with every visit.

Q: Can you describe the initial discovery of the ochre paintings at Cerro Azul? What was your reaction upon realizing the extent and significance of the rock art at Lindosa?

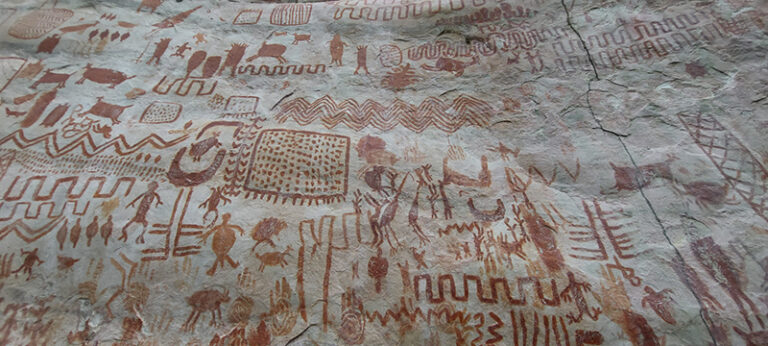

A: The ochre paintings at Cerro Azul are truly remarkable, both in their beauty and historical significance. While these artworks were first documented in the 1920s, substantial research was halted due to the region’s remoteness and Colombia’s civil conflicts involving FARC. The area was simply too dangerous to explore. However, after the 2016 peace treaty, which reopened the landscape, our Colombian colleagues eagerly returned to continue the work left unfinished since the late 1970s. They aimed to explore the known rock art and delve into the under-explored archaeology. Although our team primarily focuses on environmental archaeology, we were immediately captivated by the rock art panels. The paintings, rendered in vibrant red ochre, are breathtaking. The sheer density and diversity of the images—ranging from highly specific forms to more abstract ones—make interpreting them a fascinating challenge. We even organized a conference in the region, inviting rock art specialists from around the world, and everyone was unanimously amazed by the vibrancy and global significance of these artworks.

Q: Have the rock paintings at Lindosa been well preserved?

A: Yes, the rock paintings have been exceptionally well preserved, largely due to the durability of the ochre used. Unlike plant-based paints that degrade over time, ochre is a mineral pigment that remains stable for thousands of years. The rock shelters where these paintings are found typically have large overhangs that protect the panels from direct rain and other environmental factors. As a result, the paintings have maintained their original vibrancy and detail, allowing us to appreciate them in nearly the same condition as when they were first created.

Q: Which indigenous group primarily occupies this area?

A: The question of which indigenous group primarily occupies the area where the rock art is found is complex. There is no direct line of descent connecting the creators of the rock art to any single modern indigenous group. Today, the region is inhabited by at least four or five different indigenous groups, each with a deep connection to the land. While some of these groups have associations with the rock art, none of them directly claim it as the work of their ancestors. Instead, they offer interpretations based on their cultural perspectives, often viewing the art as representing ancestral indigenous knowledge, though not necessarily from their lineage. This lack of direct connection makes understanding the cultural significance of the rock art challenging, but it also opens up opportunities for collaboration with local indigenous leaders, shamans, and healers. These interactions have provided valuable insights into the art, enriching our scientific observations with indigenous perspectives.

Q: Have you observed changes in the environment from the time the rock art at Lindosa was created to the present day, particularly in terms of habitat and animal species?

A: The environment depicted in the rock art and the current landscape have undergone significant changes, particularly when considering the possible inclusion of now-extinct megafauna in the art. One of the most intriguing aspects of our research has been the effort to directly date these paintings, a task that is both challenging and complex. We’ve collected numerous samples, hoping to identify organic binders or other compounds in the ochre that might allow us to determine the age of the paintings. Ochre, being a mineral, must be processed into a pigment, often mixed with plant materials, oils, or other organic substances to create a stable paste suitable for painting. The lines and forms in the rock art are very precise, indicating that the artists carefully prepared their materials to achieve the desired effect. We’ve sent samples to a specialized lab in Portugal, where they are working to chemically analyze the compounds and, if possible, date them. This could provide us with a clearer picture of when these paintings were created.

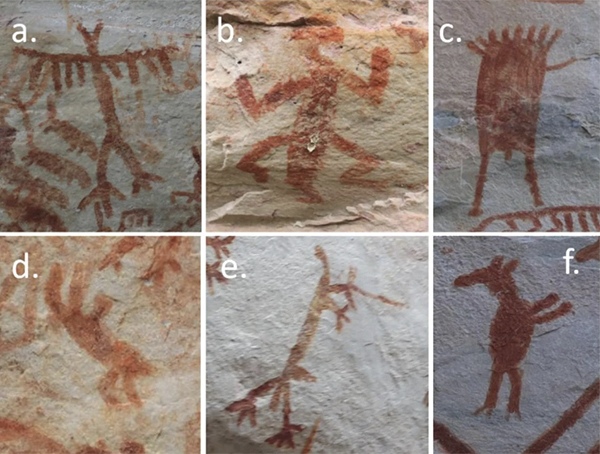

During our archaeological excavations, we discovered rock shelters with remarkably deep stratigraphy, some reaching depths of 2-3 meters. This is quite rare in tropical soils, where such deep and well-preserved layers can offer a long chronology of human occupation. Among the finds are processed ochre fragments dating back as far as 13,000 years. While we can’t yet definitively say that this ochre was used for the rock art, it is clear that people in these shelters were processing ochre over a span of thousands of years. As for the animals depicted in the art, many species still inhabit the region today, but there is compelling evidence that some paintings may represent now-extinct megafauna, such as mammoths, native horses, or giant sloths. This suggests a continuous tradition of ochre use and possibly a rich narrative of human interaction with these now-lost species. Understanding these changes and the way they are reflected in the art is crucial to our research, providing insights into how early humans perceived and interacted with their environment.

Q: The absence of big cats, despite their presence as apex predators, is intriguing. What are your theories about why these powerful animals were not depicted in the rock art at Lindosa?

A: The rarity of big cat depictions, especially jaguars, in the rock art at Lindosa is indeed fascinating. Jaguars are deeply embedded in Amazonian mythology, often seen as powerful and mystical creatures. However, in Lindosa, their representations are surprisingly scarce, which contrasts with nearby sites like Chiribiquete, where jaguars are prominently featured. This disparity suggests that different communities may have had varying symbolic relationships with these animals. While the people of Chiribiquete might have closely identified with the jaguar, viewing it as a totem or spiritual guide, the community at Cerro Azul might have had stronger connections with other animals like tapirs or bats, which are depicted more frequently. Interestingly, we see certain animals represented in specific panels at Cerro Azul, which suggests that the choice of animals might reflect localized spiritual connections or the preferences of individual artists or ritual specialists. This variation in animal depictions indicates that these communities had distinct cultural or spiritual practices that influenced their artistic expressions.

Q: Do you think that shamans played a big role in deciding what was painted on the rock?

A: We believe that shamans or ritual specialists likely played a significant role in deciding the content of the rock art. Although the rock art at Lindosa might appear somewhat crude, it still requires a certain level of expertise to produce. This suggests that not everyone in the community would have been capable of creating these images. The consistency in style across the rock art indicates that it was likely produced by individuals with specialized knowledge, possibly shamans who held a unique role in the community. Shamans are often considered mediators between the natural and supernatural worlds, occupying a distinct position within the social structure. They were believed to possess the ability to communicate with spirit beings, such as the “Master of Animals,” who governed the natural world. These ritual specialists would perform specific rituals, often in private settings, to maintain harmony between the community and the forces of nature. For example, in the context of hunting, shamans would conduct rituals to ensure a successful hunt, interpreting and conveying the rules that governed the community’s interactions with the natural world.

Q: Do you think the use of hallucinogens played a role in creating the rock art at Lindosa, particularly in the depiction of shape-shifting between animals and humans?

A: Yes, it is likely that hallucinogens played a significant role in the creation of the rock art, particularly in altering the consciousness of the artists. Among many modern indigenous communities in the Amazon, there is evidence of the use of psychotropic substances during rituals and spiritual ceremonies to induce altered states of consciousness, enabling shamans to connect with the spirit world. Rock shelters and caves, where the art is often found, are seen as gateways between different dimensions of existence, providing a space where the tangible and intangible worlds intersect. In our research, we found limited direct evidence of psychotropic drugs but did identify a single sample containing yopo, a hallucinogen. It’s also possible that altered states were induced through fasting or extreme physical exertion, which could have enabled shamans to enter a necessary state of consciousness to create the rock art. The depiction of shape-shifting between animals and humans in the art likely reflects the cultural beliefs and spiritual practices of the time, where the boundaries between humans, animals, and spirits were fluid. The rock art serves as a visual representation of these spiritual journeys and the fluid nature of identity in the Amazonian worldview.

Q: What is the role of the artists in relation to nature? Do they see themselves as superior to animals, or as part of nature?

A: Interpreting the role of the artists in relation to nature is challenging, but insights from ethnographic studies suggest that the artists, often shamans or ritual specialists, did not see themselves as separate from or superior to nature. Instead, they viewed themselves as deeply interconnected with the natural world. The role of the artist or shaman was to mediate the relationship between nature and society, conveying the rules and moral codes that governed the community’s interactions with the natural world. These rules could vary based on factors such as age, gender, or social status. The artists’ work can be seen as a guide to understanding the world around them, encoding knowledge and beliefs in a way that was accessible to the entire community. The rock art served as a visual encyclopedia, teaching and preserving the community’s knowledge about the natural world and their place within it. This idea was reinforced when local community leaders described the rock art as an “encyclopedia” of their world. In many ways, the role of the artist was similar to that of a religious leader in Western societies, such as a priest in the Christian Church, who interprets religious texts and provides moral guidance. The work of the shamans or artists was not just artistic expression but a crucial aspect of cultural preservation and spiritual communication.

Q: What were some of the challenges you faced in accessing and studying these remote rock art sites?

A: Accessing remote rock art sites in the Amazon presents significant challenges. While some well-known sites have become accessible tourist destinations with good facilities, our research has taken us far beyond these areas to lesser-known sites that required extensive surveys to uncover new rock art panels. The challenges are immense, involving trekking through dense jungle with no established trails, dealing with the typical obstacles of the rainforest, such as thick undergrowth, unpredictable weather, and humidity. The physical effort required to reach these sites is substantial, demanding endurance and preparation. Beyond the physical challenges, there are also significant socio-political issues in the region. Although the peace treaties in Colombia have opened up many areas, some regions remain unstable, requiring delicate negotiations with local communities. Building trust with these communities has been a gradual process, and we’ve collaborated with local universities to create programs that benefit the local people. For instance, we’ve established a diploma program through the University of Antioquia to provide local tour guides with formal training in archaeology and ecology. This program has been successful, with many local guides earning diplomas that enhance their ability to share accurate information with tourists. Additionally, we’ve brought some of these guides to England to expose them to heritage management practices. These initiatives are part of our broader effort to ensure that the communities living near these sites are active participants in the preservation and interpretation of their heritage.

Q: The rock art at Cerro Azul features depictions of animals and mythological transformations. How do these images contribute to our understanding of ancient Amazonian mythology and belief systems?

A: Understanding the rock art at Cerro Azul and its connection to ancient Amazonian mythology is a complex process. The images are rich with symbolism and deeply connected to the belief systems of the people who created them. One of the challenges is the lack of a direct cultural link between the creators of the rock art and modern indigenous groups, making it difficult to interpret the meanings behind these images. To navigate this, we rely on ethnographic studies of contemporary Amazonian groups, identifying recurring themes in Amazonian myths that resonate with the rock art depictions. For example, many myths involve animals with human-like qualities that serve as moral guides for the community. These animals occupy a space between the human and animal worlds, embodying traits that provide ethical lessons. Interestingly, what is not depicted can be as telling as what is. For example, the absence of jaguar depictions might suggest that the animal was considered too powerful or sacred to represent, much like the Islamic tradition of not depicting human figures. This raises the possibility that certain animals were deliberately omitted from the art because they were seen as possessing a power that could not be safely controlled or depicted.

Q: How do the proportions of animal remains found at excavation sites compare to the animals depicted in the rock art? What might this tell us about the symbolic importance of certain animals in these communities?

A: The relationship between the animals depicted in the rock art and the animal remains found at excavation sites offers valuable insights into their symbolic significance within ancient Amazonian societies. The animals depicted in the art do not always correspond directly to the species most commonly consumed or found in the archaeological record. This suggests that the significance of these animals was not solely based on their role as a food source but also on their symbolic or spiritual importance. Every animal, regardless of its size or abundance, could hold symbolic value within the community’s mythology and cultural practices. For instance, fish play a crucial role in the diet of modern Amazonian communities, yet they are depicted far less frequently in the rock art at Lindosa. This could indicate that while fish were essential for sustenance, other animals held greater symbolic importance. Birds, for example, are often depicted in the rock art and hold a special place in many cultures due to their ability to fly, symbolizing freedom or the soul’s journey. The presence of crocodiles, turtles, and other aquatic animals in the rock art at Lindosa highlights the diverse environments these communities navigated and revered, reflecting their deep understanding of and connection to the natural world.

Q: Can you elaborate on the ecological knowledge reflected in the diverse array of animals depicted in the rock art? How did ancient Amazonians’ understanding of their environment influence their artistic representations?

A: The rock art of the Amazon reflects a deep and sophisticated understanding of the diverse ecosystems that ancient Amazonians inhabited. The region where we are working is particularly fascinating because it sits on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, close to the savannahs to the north and the dense tropical forests to the east. This location provided access to a wide variety of environments, each offering different resources and challenges. The art in these regions encapsulates this diversity, representing animals and plants from both the savannah and the rainforest, as well as from the rivers and flooded forests that crisscross the landscape. This breadth of representation suggests that the ancient Amazonians were not only skilled hunters and gatherers but also keen observers of the natural world. They understood the intricacies of their environment, from the behavior and habitats of various animals to the seasonal changes that affected their availability. This knowledge is reflected in the detailed and varied depictions in the rock art at Lindosa, which serve as a visual record of the animals, plants, and landscapes that were important to their way of life. Despite the rich biodiversity of the region, it is intriguing that we do not see the same kind of large-scale societal developments that occurred in other parts of the Amazon, such as the construction of monumental architecture. One possible explanation is that the abundance of resources allowed the communities to maintain a relatively egalitarian and mobile lifestyle without the need for hierarchical structures. The rock art reflects a society that was deeply connected to its environment, focusing on animals and the natural world rather than imposing human dominance through large-scale construction. The scenes of transformation, where humans are depicted as merging with or becoming animals, further highlight the fluid boundaries between the human and natural worlds, a concept central to many Amazonian myths.

Q: Could you elaborate on the scope of the study and the specific panels of rock art that were analyzed?

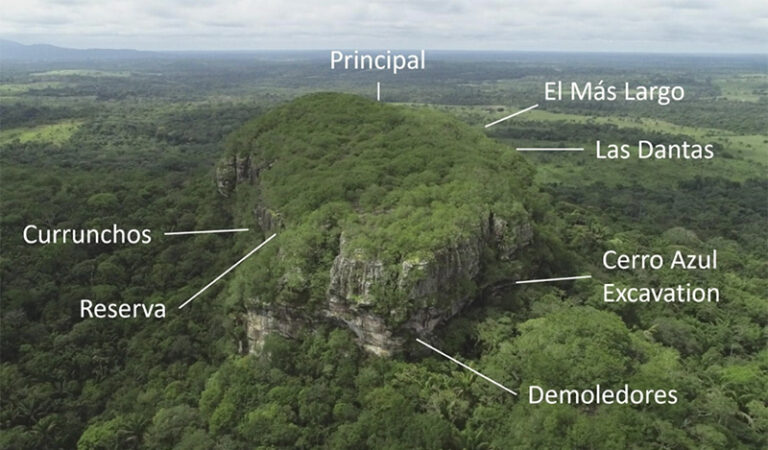

A: The study, conducted by researchers from the University of Exeter, Universidad de Antioquia in Medellín, and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, focused on analyzing six specific panels of rock art in the Colombian Amazon. These panels varied significantly in size, with the largest being El Más Largo, a 40-meter-by-10-meter panel that contained over 1,000 images. On the other hand, the Principal panel, though smaller at 10 meters by 6 meters, featured 244 images that are remarkably well-preserved and display vibrant red hues.

In total, we cataloged 3,223 images using both drone photogrammetry and traditional photography techniques. These images were categorized based on their form, with figurative images being the most prevalent, making up 58% of the total. Among these figurative images, over half are related to animals. We identified at least 22 different animal species depicted, including deer, birds, peccary, lizards, turtles, and tapirs.

The ancient rock art of Cerro Azul provides a profound window into the lives, beliefs, and ecological knowledge of the earliest inhabitants of the Colombian Amazon. These ochre paintings, preserved for thousands of years, not only document the rich biodiversity of the region but also reflect the deep spiritual and cultural connections between the people and their environment. Through the meticulous work of Dr. Mark Robinson and his team, these artworks have been brought to light, offering invaluable insights into the complex relationships between humans, animals, and the natural world. As we continue to study and interpret these images, they remind us of the enduring power of art to bridge the past and present, offering a glimpse into a world where the boundaries between nature and humanity were fluid, interconnected, and deeply revered.