Curtis Benzle's Artistic Voyage: Refining the Elegance of Colored Translucent Porcelain

Curtis Benzle’s journey in the world of ceramics is a captivating narrative that began at Hillsdale College, Michigan. Guided by the expert hand of Bert Fink, Benzle delved into the traditional art of hand-building in ceramics, kindling a lifelong devotion to this expressive medium. His scholarly path led him to Ohio State, where, under the astute mentorship of Takao Sakuma, he cultivated his craft through observant practice, prioritizing the tactile and practical over the theoretical.

The apprenticeship with Robert Eckles in Wisconsin marked a significant chapter in Benzle’s career, focusing on the refinement of his hands-on skills in pottery. His artistic curiosity was then drawn to the Rochester Institute of Technology’s glass program, captivated by the vivid clarity and transparency of glass. However, it was the rich, tangible quality of clay that called him back, leading to the establishment of his own studio in South Carolina. In this creative sanctuary, Benzle began to explore the fusion of glass’s luminous qualities with the tangible essence of clay, a vision that reached its zenith at Northern Illinois University. Here, he pioneered a unique form of translucent porcelain and the intricate colored clay process known as nerikomi, harmonizing his artistic insights with groundbreaking techniques.

Benzle’s artistic journey is a testament to his unyielding dedication to marrying aesthetic sophistication with innovative artisanship. As we explore his journey and the evolution of his creative process and philosophy, we engage in a thoughtful conversation with Benzle, uncovering the inspirations and challenges that have honed his expertise in colored, translucent porcelain.

Background: You mentioned your initial fascination with throwing on the potter’s wheel led to a lifelong obsession with clay. Can you elaborate on this part of the journey?

My fascination with clay did not actually begin with the potter’s wheel, but with traditional hand building under the instruction of Bert Fink at Hillsdale College, a small liberal arts school in Michigan. I was not a particularly good fit with Hillsdale, as even then it was developing into a bastion of conservative thought. However, prior to departing for Ohio State, I decided to take one last semester’s worth of courses for enjoyment rather than degree requirement. These included Ceramics. Professor Fink brought me on as his assistant during that summer and I made clay for all his classes. I enjoyed making the clay as much as making pots. They were a wonderful synthesis of chemistry and creativity.

By the time I arrived in Ohio State, I was committed to clay and fortunately Ohio State had an excellent Ceramic department at that time. My first OSU ceramics instructor was Takao Sakuma. Mr. Sakuma did not speak much English, which was perfect as it forced me to learn by observation and repetition. As my Fine Art, undergraduate peers worked on images, attitude and novelty, Sakuma encouraged me to build my skill.

Following graduation, my ceramic education continued under an apprenticeship to Robert Eckles in Bayfield WI. Away from the competitive chatter of an undergraduate education, I continued along the path initiated by Takao Sakuma. I threw thousands of pots as my skill and acceptability ratio improved slowly from near zero to probably 75%.

Can you tell us more about how this journey began and what specifically drew you to porcelain and its translucency?

After my apprenticeship with Bob Eckels, I enrolled in the glass graduate program at the Rochester Institute of Technology / School for the American Craftsman. I had studied glass at OSU and was fascinated with its vibrant coloration and transparency. While I loved the appearance of glass, the near total absence of tactile involvement was problematic. I left the glass program after one year and opened a clay studio in South Carolina. During my two years there, I made pots, but started to wonder how I could possibly integrate the luminous quality of glass with the tactile character of clay AND develop a way of working that would synthesize the forming and decorating processes in much the same manner as glass, weaving and basketry. I was accepted to the graduate program in clay at Northern Illinois University and I spent the first year and a half of my time there developing a highly translucent clay body and materials and processes to incorporate color directly into the clay. Because this exploration predated the availability of Mason stains, I tried anything that had color in it… oxides, glaze stains and underglaze. Eventually, I found materials to create a pink, blue and yellow that combined the ability to withstand 2,300 F and maintain the translucency of my new porcelain body.

As a more direct answer to your question about what drew me to porcelain and translucency……the image had been in my mind all along. I knew exactly what the materials and resulting objects should look like. It was more a matter of discovering and inventing specific methods and materials to transform my imagination into reality.

Q: Source of Inspiration: In your journey as an artist, what have been your primary sources of inspiration, particularly for your work with translucent porcelain? Are there any specific experiences, artists, or aspects of nature that have significantly influenced your artistic vision and creation?

While I have learned much from many artists, I cannot say that I have ever felt that any single, contemporary clay artist has been particularly inspirational. Perhaps this is because I have never seen anyone who works the way I do. But it is more likely because from the beginning my inspiration has been essentially personal.

A good example of how this personal vision has led me to develop required techniques can be seen in how I developed my “nerikomi” method. Initially, I referred to the process as “millefiori”, as I had seen that technique used with glass. From there came the idea to try it with a tactile medium—porcelain.

Because the materials, glass and porcelain, are quite different to work with, I needed a new technique. To develop specifically how this might work, I researched methods used by confectioners to make Easter candy. Fortunately, there was such a confectioner in Columbus, OH and I asked him how he made his candy. He had a series of dies made for each of the individual shapes required for his image and, once the dies were made, he then forced molten candy through the dies. Once he had all the individual parts made, he assembled them, reheated the assembled image and voila!, he had his millefiori Easter candy—and I was on my way.

The primary difference was that porcelain was more malleable and stable than molten candy and this opened the door to a far greater range of color manipulation for me.

In terms of contemporary artists, Richard Marquis in glass was an inspiration, but glass differed from porcelain in much the same way that candy did. Still, the impact of his finished objects was inspirational. Historically, Imari-ware and Imperial Russian porcelains continue to amaze me.

I have always been inspired by nature and during introductory presentations I usually show the connection between those things I have seen and things I have created. Even though I find many experiences in nature to be highly inspirational, I have never felt compelled to specifically replicate anything I have already seen.

……………….OK…………. at one point many years ago I did have the idea to try to replicate shells. It was an interesting challenge, and I was pretty successful. However, it was also very instructive in that when I was finished with my replication, I was left with a shell that looked precisely like a shell I could purchase at any beachfront shell store. Inspiration yes but copy no.

One more valuable inspiration comes from life experience. Early in my career, I used to introduce this inspirational connection as part of my artist statement. Although it is honest and accurate, I discovered that most audiences found the concept difficult to comprehend or connect; so I stopped using it in my artist statement. I have included it here so you can decide for yourself.

Artist statement-Curtis Benzle

My art has not seemed to change much. Characteristics that defined my work twenty years ago; color and light, remain as the obvious visual evidence of my self expression.

In a world so ripe with aesthetic challenge, I too wonder at this dogged consistency. Wonder; until I remember that this “self expression” is in reality more of a personal mission—not so much about me, but more about understanding and uncovering an expression of Beauty. My seeming consistency is, in fact, only evidence that I believe I am on the right path and that deviation at this point would be the same as giving up that quest.

“Beauty”? That’s a great example of a single word being asked to do too much. Clearly, I am following a very personal definition of “Beauty”. A definition that is best explained through a story…

Many years ago I was conducting a workshop about my art—techniques and purpose. As an introduction, I was attempting to explain the aesthetic motivation behind my work and I was not making much headway. This wasn’t an audience of accomplished artists or even ambitious art students. They were mostly mothers. Women who had taken a significant “time-out” to raise families and were now returning to their art making roots.

Noting their growing frustration with my art-speak and our shared passion for parenting, I tried to relate my aesthetics through that common bond. After asking if they had children(almost all had) I asked them to recall one of those days when the kids had tested every last bit of their patience. From their expressions I could tell this was not a first choice for much of my audience but they obliged. Then, I continued, try to remember that moment about twenty minutes after the last scolding, when you had finally succeeded in subduing them in bed. Remember wondering if they really were asleep or just plotting their next move. Remember tiptoeing down the hall and silently cracking open the door; letting that shaft of light fall across their now sleeping and angelic faces. And then, remember how you felt as you savored that quiet moment. The sweet smile, the gentle breath, the sense of peace, comfort and security. It’s a feeling that defies words and it’s that feeling that fuels my aesthetic efforts.

There is a reason I struggle with difficult materials, invent frustrating techniques and tolerate relentless failure. For me, the reason is an unfailing desire to give form to feeling. An attempt to connect myself, and my audience, with a “better place”. To express some of what is so wonderful in the world.

That goal has been both elusive and seductively possible. Porcelain, pattern, color and light are some of the keys available to aid me in unlocking this Beauty. While finding the right sequence and order may challenge, every success leads me further down the same path and excites my passion to continue the quest.

Technical Challenges: You have discussed the complex process of creating translucent porcelain. What were some of the biggest technical challenges you faced in developing your unique Benzle #89 recipe, and how did you overcome them?

When I set out to develop a translucent porcelain in 1973, there was surprisingly little technical information immediately available. The standard porcelain clay body then was 25% kaolin, 25% ballclay, 25% feldspar, and 25% silica. This resulted in a white clay, but certainly not a translucent clay.

Rudy Staffel was working in translucent clay and I contacted him for assistance. He advised me to take everything out of the standard recipe that was either a clay or an opacifier. I followed his advice and soon realized that a clay body without clay is glass. I began to reintroduce the purest forms of clay, specifically Grolleg kaolin, and the resulting material was somewhat translucent but very non-plastic. Rudy advised me to use potato starch to increase the plasticity. I’m not sure if that was a joke or not, but the resulting stench in my studio, as the starch rotted, was unbearable. Further exploration led me to “v-gum t”—-an industrial plasticizer.

Over the years I have continued to test porcelain bodies in the pursuit of perfection, but at this point I am comfortable with the characteristics and even the shortcomings of my #89. It is prone to cracking and difficult to manipulate, but also incredibly white and highly translucent.

I recently developed a nice porcelain that is easier to use and less prone to slumping–# 108.

Years after I finished developing #89, I found an article by Robert Tinchane about translucency and porcelain. While at that point the information served primarily to confirm what I had discovered, it is still very interesting.

*Note: You can reach out to me at curtisbenzle@gmail.com for the aforementioned information.

Artistic Process: How do you balance the technical aspects of working with translucent porcelain with the artistic expression you aim to achieve in your pieces?

Finding this balance was never particularly difficult because the technical aspects of my material were always in service to my artistic vision. Earlier in the interview, I discussed how I developed my version of the nericomi technique. The reason why I developed this technique was because I desired a way to create specific, graphic images and patterns that were not subject to the fluid movement of glaze.

Other aspects of my work follow a similar pattern; artistic vision demanding a technical solution. Perhaps the best example of this, or maybe just my favorite example, is my use of kintsugi technique. I was always fascinated with ceramics from the Muromachi and Momoyama periods in Japan, but I never really understood how that fascination could find relevance in my work.

Over the years, it was quite apparent to me that my #89 porcelain clay body was very prone to cracking. For years I would tediously repair the cracks by packing the fissure with calcined porcelain and refiring the piece at a higher temperature until the crack was eventually filled in and invisible. This process never felt particularly satisfying and I eventually concluded that just as the artists of the Muromachi and Momoyama periods emphasized the inherent characteristics of their clay, I should be emphasizing the natural characteristics of mine, instead of performing cosmetic repairs.

There was a bit of a learning curve/ gap between that revelation and the solution of how to integrate inherent characteristics of my #89 porcelain with my way of working. The solution, kintsugi technique, was not widely used in the early 1980’s, and, because I did not know the specifics of traditional “urushi lacquer” practice, I took it upon myself to invent a technique. Instead of the traditional materials, I used five-minute epoxy with gold leaf and there is a funny story that goes along with my “kintsugi education”.

Excerpt below from Pottery Making Illustrated:

“Once I decided to accentuate and embellish cracks, I still had to figure out how to do it. Kintsugi had yet to make its way into the American clay vocabulary and “Googling” was not an option. Photographic observation led me to believe that historic cracks had been filled with molten metal. A confusing and quite frightening concept for sure! Moving on to readily available, 20th century technology, I pondered a less dangerous option…five minute epoxy and gold leaf. As I perfected my technique however, I was consistently haunted by the nagging thought that I was “faking it”. This pernicious thought persisted until, as fate would have it, I was awarded a residency in Seto, Japan—one of seven original Japanese kiln sites and a renowned center of porcelain production.

During a personalized tour of the Aichi State Museum of Art with the head curator, I seized the moment and asked if he would please share their technique for repairing cracks?

The curator responded, “Ah, Benzle-san”. “We use [sic]’phiminopochi’. As I struggled to remember this new Japanese word, I pressed on. “Once you have applied the ’phiminopochi’ material to the cracked area, how long does it take for the material to set. Thankfully I was in Japan! As the curator kindly continued, he smiled and said, “Ah…..Benzle-san….of course….five minute”! We shared a good laugh and I was left with a clear conscience concerning my repair technique.

Lithophanes: Your work with lithophanes, especially integrating digital technology, is fascinating. Could you explain how the transition from traditional methods to using CNC routers and digital printing has influenced your artistic approach?

Of course, there is much more to this topic than meets the eye. Within the topic of “traditional methods”, there are several technological upgrades that I went through. You can see below as I wrote for Ceramics Monthly:

Lithophanes

My initial exposure to lithophanes came when I was an undergraduate student at Ohio State University in 1970. Prof. Margaret Fetzer maintained the OSU Ceramic Department library (which included an extensive ceramic collection) and, learning of my interest in porcelain, Mrs. Fetzer ignited my interest in translucency by revealing some lithophane treasures hidden away on a back shelf.

It wasn’t until 1974, however, when I decided to attend graduate school at Northern Illinois University under Gib Strawn that my early interests actually bloomed into a body of work. My first experiments with translucent porcelain utilized stamping and carving to vary the porcelain wall thickness and reveal the transmission of light. In short order I added the use of ceramic stains and the nericomi process to develop translucency based pattern in my work.

I didn’t revisit actual lithophanes in earnest until I moved back to Ohio in 1979 and met Laurel Blair in Toledo. Mr. Blair was surprised and excited to find a ceramic artist to share his passion for translucent porcelain and he encourage me to reproduce selections from his enormous collection as a commercial product. I declined Mr. Blair’s generous offer, opting instead to create a line of original lithophanes that incorporated traditional carved wax techniques with my ongoing interest in stained porcelain.

Following further research at the OSU Ceramics library, I met Mr. Walter Ford in 1982. Walter Ford had received a Master’s degree in Ceramic Engineering to compliment a lifetime involvement in the ceramic industry. Mr. Ford completed extensive research on the subject of photographic techniques and ceramics that resulted in his paper, “Application of Photography in Ceramics” that was printed by the American Ceramic Society in January, 1941. In his paper Walter Ford references the use of photo-mechanical processes in the production of ceramic products dating back to the early 1800’s.

Using Mr. Ford’s paper as a jumping off point I did additional research on photomechanical processes* that resulted in my own development of a technique for creating lithophanes using photographic images.

The technique for making a photographic plate with sufficiently deep relief to generate a plaster mold is surprisingly similar to the relatively well-known technique used in gelatin plate printmaking. The primary modification is the addition of a dichromate that will make the gelatin solution photosensitive. Either potassium or ammonium dichromate** can be used with the primary difference being that ammonium dichromate is slightly stronger.

A good starting point for experimentation would be: 100 gm Knox gelatin (unflavored), 2.5 gm ammonium dichromate, 300 cc water. Slowly heat the mixture until melted (heat slowly and avoid over-heating the mixture). Once melted, pour the fluid onto a sheet of 1/4” plate glass surrounded by a 1/4” reservoir of plastilin. Dry the plate in total darkness (I used my dehydrator). Once dry, place a negative on top of the gelatin mixture and expose under photo lamps (exposure times vary but start with 30 minutes). Wash the exposed plate under water to reveal the relief image. A plaster mold may then be pulled from the gelatin plate.

Interestingly, shortly after I uncovered the mystery of photographically produced lithophanes, my interest in the photographic process soon waned. Despite the intense tedium of the carved wax technique I find the original, and essentially human, marks produced to be favorable to the reproductive quality of even the finest photo-mechanically produced lithophanes. Accordingly, all of the lithophanes and translucent porcelain objects I have created over the past fifteen years have been developed using the time honored, carved wax technique.

*”The Keepers of the Light” by WM. Crawford, Morgan & Morgan, 1979

“Alternative Photographic Process” by Kent E. Wade, Morgan & Morgan, 1978

“A Unique Experience-Gelatin Plate Printmaking” by Fran Merrit & Nancy Marculewicz, unpublished 1974

** Both ammonium dichromate and potassium dichromate are likely to cause skin irritation. Rubber gloves and a respirator should be used during the entire plate making process.

Using a CNC router to create the molds for making a lithophane has had two major impacts on my artistic approach. It is faster and it requires less hand skill than any process that preceded it.

Because there is virtually no hand skill involved, when using a CNC router, I don’t even do it myself. I hired a professional graphic illustrator with wonderful knowledge of Photoshop and other image generation software. I provide the positive image and he returns the image in Corian plastic. I turn that plastic version into a plaster mold, which is used to form the porcelain.

I have included one piece that I made using this technology- a sculptural lighting piece illustrating my family. I have several product ideas using the CNC router, but the substitution of a machine for hand skill has pretty much sapped my enthusiasm artistically.

My fascination with the luminous quality of porcelain continues unabated—only enthusiasm for the machine generated lithophane imagery has been diminished.

Cultural Perception: You mentioned that translucency in porcelain is often overlooked in the art world. Why do you think this is the case, and how do you believe this perception can be changed?

I think translucency is overlooked in the art world because it is subtle. The finger mark on a hand-glazed pot is subtle, and usually overlooked or undervalued, when compared to more efficient glazing techniques. For that matter, almost anything I can think of that requires exceptional skill is overlooked by the art world.

We seem to have an art world that is primarily focused on novelty and overt self-fascination. A well-constructed personal “story” has seemingly displaced the value of subtlety and skillful execution. A well-constructed story is entertaining and easily understood. Skillful execution requires study, experience, knowledge and enthusiasm to search for the subtlety of a sensitive human touch.

Quality education and committed students provide a ready avenue for change. I do see some enthusiasm for this path but unfortunately, not emanating from the established art world.

Future of Porcelain Art: Where do you see the future of porcelain art heading, particularly in terms of integrating modern technologies with traditional techniques?

Modern technologies are fascinating and provide incredible opportunities for creative self-expression and beauty. In order to fully realize the potential of modern technologies, I think it is critically important to initially define the differences between modern and traditional methods.

Co-existing with the limitless potential of the “new”, there is great beauty and cultural relevance in traditional techniques. The value of human touch as it relates to the creation of art objects is a critical center point to this concern.

Both a synthesized voice and a human voice possess infinite possibilities for creative expression, but they are not the same. A synthesized voice is engineered, while the skilled human voice is perfected through training and practice. Both have value but are quite different in what they offer us.

I previously addressed this issue in an article for Garland Magazine.

Personal Favorites: Among all the pieces you’ve created, do you have any personal favorites or ones that hold special significance to you? Can you share the stories behind them?

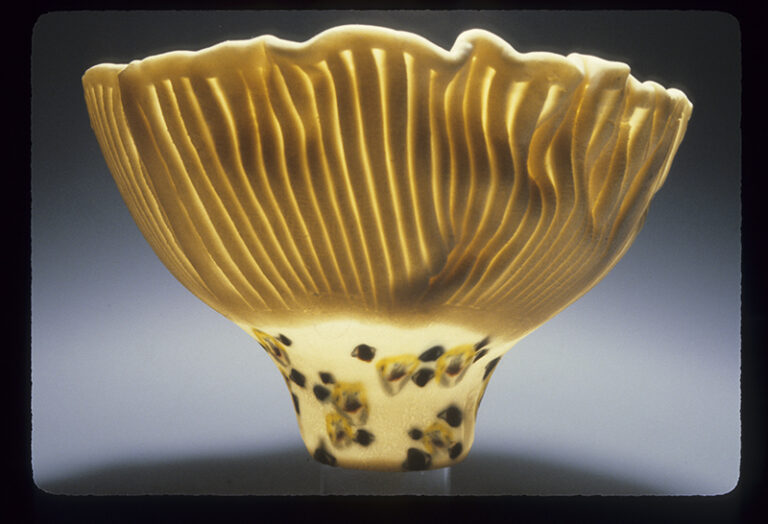

I have attached two favorites; A vessel and a lighting piece.

I like the vessel because it comes very close to achieving the image of beauty I have persistently pursued. The specific imagery provides an accessible entree into the pursuit of a deeper awareness of the object. A more complete understanding is dependent on the luminous environment, as there are many aspects visible only when backlit. The coloration and composition are, for me, serene and comforting. In the end, this piece does what I believe is crucial for visual art to do, by providing an emotional experience that is difficult to quantify or verbalize.

The lighting piece, despite its dramatically different scale, does much the same. This piece is in our kitchen and runs for twenty feet just beneath the eleven-foot ceiling. The imagery is composed of leaves, with a supporting cast of various “leaf environment” characters including frogs bugs snakes and lizards.

Visitors to our kitchen are rarely aware of the piece until they’ve been in the space for a while. Inevitably, they become aware of the soft illumination emanating from above and look up. As with so much of what we see in nature, the specifics of the piece are initially elusive. Over time and with further observation however, they are provided with a similar fascination to what we may experience in nature, as tiny creatures dart in and out of our awareness. Again, as with the vessel, my desired viewer response is an intentionally, non-verbal experience.

Inspiring the Next Generation: How do you hope your work and research in translucent porcelain will inspire or influence the next generation of ceramic artists?

After 50 years I have learned to not anticipate anything about how what I say or do may impact or be interpreted by anyone else. My research and work in translucent porcelain has been primarily personal and for my own benefit. I have tried to share generously and do hope that some of what I have done will benefit others. My work has been public and published and with that in mind it would be wonderful if my pursuit of positive imagery enhanced people’s lives and encouraged a sense of well-being.

Many years ago, after a collector lecture I presented at the Exhibit A gallery in Chicago, I was bemoaning my observation that some audience members were apparently dozing off during my talk. Alice Westfall (Exhibit A’s founder and a great gallerist) advised me that in any communication, if you reach even one person with your intended message, you have succeeded. Setting the bar incredibly low was an act of great kindness by Alice and one which I continue trying to achieve.

XXXXX

In summary, Curtis Benzle’s journey in ceramics exemplifies a blend of passion and innovation. From his foundational experiences at Hillsdale College to pioneering the colored translucent porcelain and nerikomi technique at Northern Illinois University, Benzle’s career is a testament to his relentless pursuit of uniting aesthetic beauty with groundbreaking craftsmanship. His work, transcending traditional boundaries between glass and clay, marks a significant contribution to the world of ceramic art.

Benzle’s website