From Wall Hanging to Tableware – The Appeal of Washi

Mr. Tsuyoshi Umeda, aka Ume-san’s shop was opened in 1893 by his great-grandfather as a “Hyogu-Shi” (a craftsman who pasted paper on the frame). He is currently the fourth generation to specialize in Japanese handcrafted paper, “Washi”.

He dyes the paper and goes through a lot of processes to create various works of art.

His warm-toned pieces are the result of his personality and the techniques he has developed over the years.

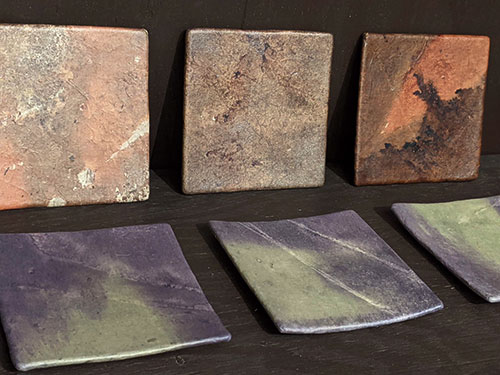

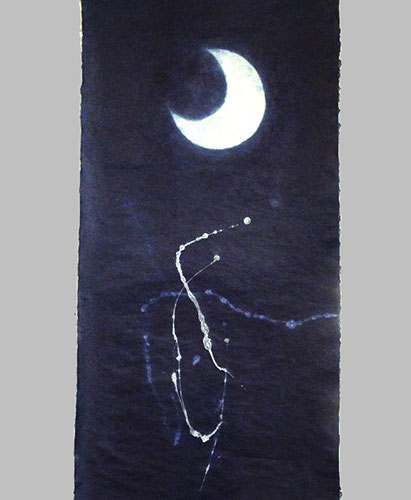

He uses natural dyes such as persimmon tannin, indigo, and Sumi ink, and applies lacquer to the washi. The mysterious shades of green, purple and black are made of “Sumi” ink with his own dyeing method.

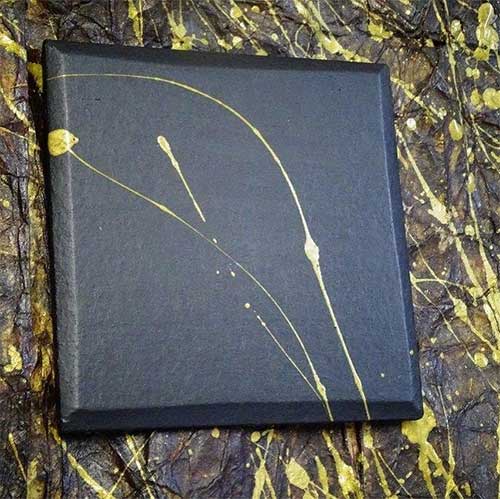

He has also developed a technique for washable and sustainable Japanese tableware, as well as expressing a metallic texture. Ume-san has been presenting the appeal of Washi in a new way.

In his shop, he sells dyed Washi itself and his handcrafts made with dyed Japanese paper, tapestries, boxes, trays, etc.

We interviewed Ume-san, who creates new techniques while maintaining tradition.

Q: You have developed water-washable tableware, how do you make paper that is water-resistant?

A: This is made possible by using craft lacquer for waterproofing. It took me 20 years to get the materials I wanted.

Q: Can you tell us about events from your childhood that led you to the present day?

A: My great-grandfather was a “Hyogu-shi”. Moreover, I grew up in a house where many pieces of papers were always around me.

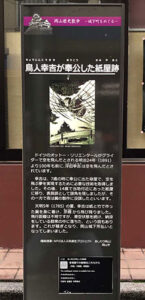

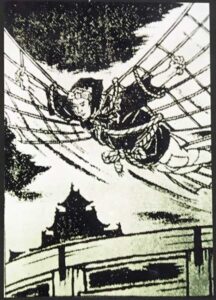

By the way, in 1785 during the Edo period, there was a paper store at the place where my shop is now located. Mr. Kokichi who worked there, known as “Bird-man Kokichi,” researched the mechanism of birds flying and applied the techniques of a “Hyogu-shi” to make wings made of washi paper and bamboo to fly from nearby Kyobashi Bridge. The fact that he lived in the same place as “Hyogu-shi” and challenge himself gives me a sense of destiny.

Q: What do you enjoy in your current job the most?

A: I love Japanese paper and natural dyes such as persimmon tannin. I like making things by hand.

The process of dyeing washi is profound, and it is also fascinating to me that creating something beautiful beyond my ability. Dyeing is my favorite part.

Q: What do you think is the most difficult part of your job?

A: Determine what meets the needs of the world.

No matter how good we think our work is, it has to be objective and sought after by many people.

And to make sure that the beauty that comes from the accident of dyeing doesn’t end up being a miracle piece, but rather a consistent, equally beautiful one. – It is the repetition of that experiment and failure. We need to have a tough spirit not to be humiliated by failures because things often don’t go as we want them to.

Q: How did you become a Washi artist? Also, you trained as a “Hyogu” craftsman, how does that help you now?

A: I like nature and I went on to study agriculture at university, but I gave it up when I realized farming wasn’t for me. I also wanted to work as a writer, but I failed at all the newspaper journalist jobs. I couldn’t find a job, so I decided to take over the family business.

Before I took over my family business, I went to study under my great-grandfather’s apprentice, Mr. Takahara (who was over 80 years old at the time, 30 years ago) for 8 years. And I learned the basics of traditional screens, which was my master’s specialty, I started dyeing Washi to make my own unique screens, and my master blessed me by recognizing my innovative work. Thus I started dyeing Washi and making Washi crafts such as tapestries, boxes, trays, and so on.

I will treasure this experience for the rest of my life because I learned the interesting and profound aspects of Washi crafts and, most importantly, the techniques of applying and processing Washi. I can apply it to many things.

Q: Do (Did) you have any other activities besides your work?

A: I had a radio program once a month for eight years until spring 2020 at FM Okayama and we introduced the various artists and crafters.

Next month, I will give a workshop at the Niimi Art Museum in Okayama. I’m going to give a talk on Washi at that time.

Q: What kind of thing do you want to challenge in the future?

A: Brush up my writing skills and write about the goodness of Washi, the interesting aspects of Washi craftsmanship, etc. I want to pass it on to the next generation with words that can be understood.

I also like to connect people, so I want to connect young artists and crafters to the media. It would be great to introduce them to the world.

As a Washi artist, I am always looking for ways to respond to the needs of galleries and customers.

Q: What is the most important thing you do as a washi craftsman?

A: Washi is something that can be used for many years. Japan’s oldest washi is in the Tōdai-ji temple’s treasure house from 1000 years ago.

So even if the washi was made recently, the good ones usually last for 100 years or so.

As for the ones made of Washi and natural materials (such as wood), the more you use them, the better they will taste. If it breaks or damaged, you can fix it and use it.

Anyway, I want to make things that can be used and loved for many years.

Handcrafted products are not finished when they are created, but rather they are handed over to the customer and used by the customer. Long-time use gives an additional charm to them.

Q: What do you want to tell the younger generation?

A: I want to share the benefits of handwork with young people. Handwork is something you learn to do, and you learn by doing.

Don’t be afraid of making mistakes, don’t push yourself, and learn steadily. It takes time, but the skills you learn will not be betrayed. It will be useful in many situations. It will help you.

The more skills you acquire, the more you will like your work, and the more you will enjoy your work.

Umeda’s Facebook