Fusing Art and Science: Małgorzata Lisowska's Exploration of Healing Through Microscope Photography

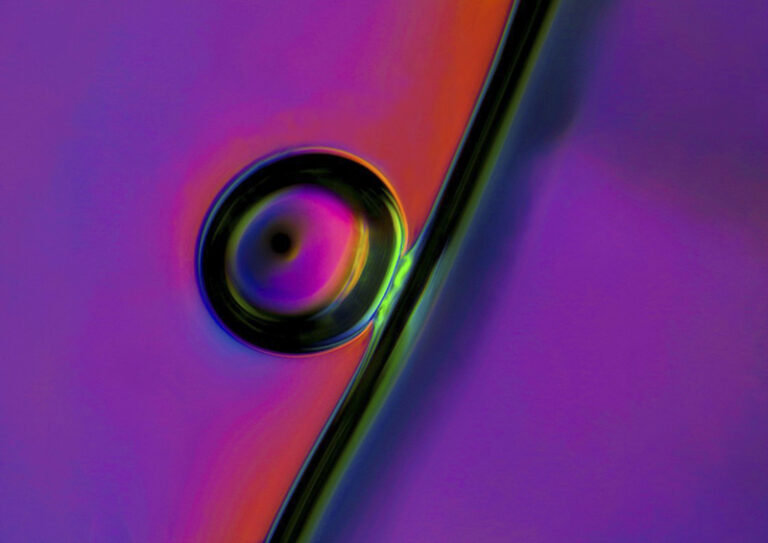

Małgorzata’s fascinating story unfolds at the confluence of art and science, highlighting a voyage driven by both a keen interest in artistic exploration and a rigorous scientific approach. This journey was ignited by a deeply personal and significant challenge—the diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in the early months of 2023. Confronted with such a hurdle, Małgorzata turned her gaze towards the microscopic world, transforming the cells of her own cancer into a subject for artistic exploration. This groundbreaking method not only secured her a distinguished third place in the Nikon Small World competition towards the end of 2023 but also symbolized a significant mark of perseverance, escorting her through the demanding journey of 16 chemotherapy treatments and surgery towards remission, or as she puts it, a restoration of health.

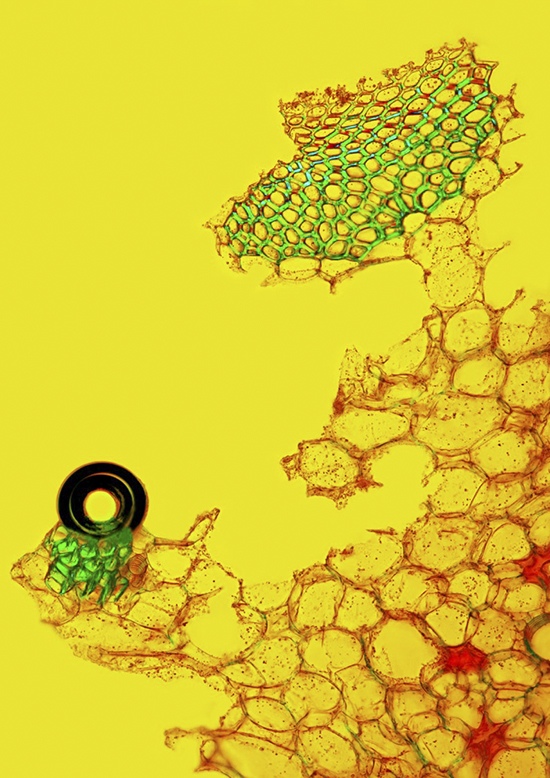

Her fascination with the microscopic realm was sparked well before this personal health challenge, during her professional interactions within the medical diagnostic field. It was in this context that Małgorzata discovered the compelling impact of visual imagery in medicine—a sector she was deeply passionate about transforming. Microscope photography served as her conduit between these realms, allowing her to uncover and showcase the hidden splendors of the microscopic world through the lens of scientific accuracy and artistic appeal. Małgorzata’s ambition is to elevate these microscopic images from their role as scientific tools to esteemed works of art featured in galleries, making the invisible wonders of our universe visible to a wider audience.

In the ensuing interview, Małgorzata recounts her own experiences of resilience, her navigation through health challenges, and her dedication to the art of microscope photography, offering a personal glimpse into her remarkable and motivational journey.

Małgorzata, could you share with us how your journey in both art and science led you to the intersection where you use microscope photography to explore the micro-scale world, particularly focusing on human cells?

At the end of February 2023, I was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). I tamed the diagnosis and the disease by looking at my cancer cells under a microscope. I took a picture of my cancer and I won third place in the Nikon Small World competition in October 2023. I went through 16 chemotherapy treatments, and a surgery. I am in remission, but I prefer to say that I am healthy.

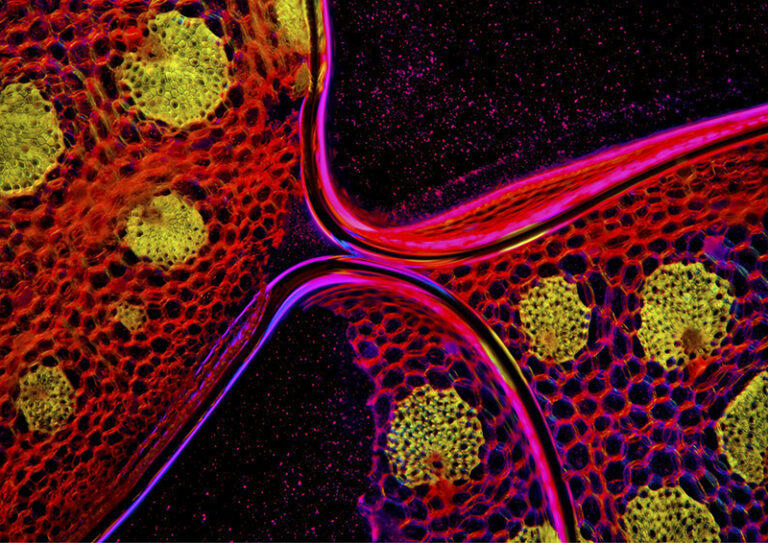

More than three years ago, when I was working with diagnosticians, I became aware of microscope photography. I realized that with it I could contribute to changing the visual layer in healthcare, which I knew all along I would like to change, but I didn’t know how. I started learning microscope photography and imperceptibly fell in love with this cosmic world it shows us.

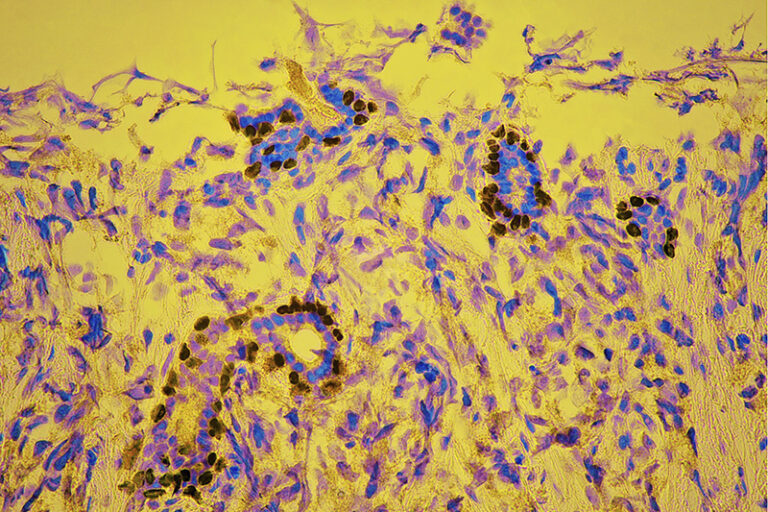

Microscope photography is a form of art for me. My purpose is to take it from the laboratory space to the art gallery. Although it is extremely niche in itself, I dream of making my art accessible to a wide audience. Through microscope photography, I intend to address a variety of themes, including but not limited to disease, as can be seen from my previous series of photographs. I would like to show a world that is not available to everyone with the naked eye. In my opinion, microscopic photography provides an opportunity to show a variety of taboo subjects that we turn our heads away from (or simply don’t see) in an engaging way.

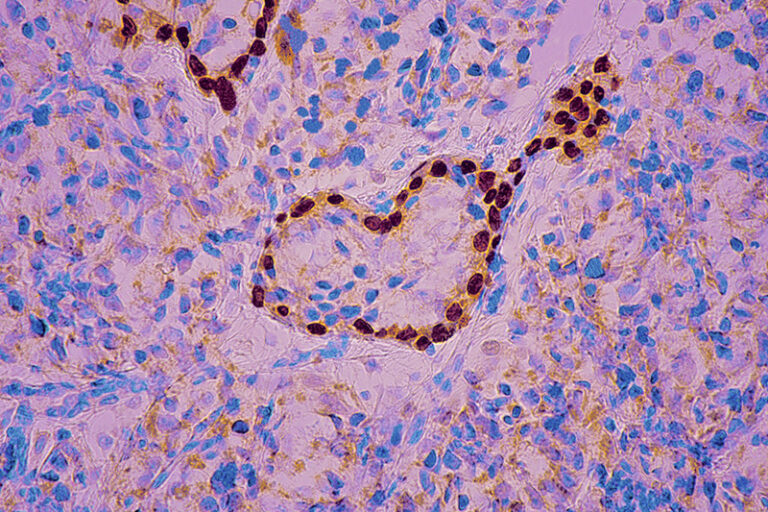

Now, I’m starting to use microscope photography as a tool in my work with cancer patients and those who accompany patients through the treatment. Behind every photo of human tissue is a different story. It’s thousands of words hidden in a single frame. Especially now, working on the latest series of photos, related to cancer cells, I feel the need to share my experience with others. To inform about what helped me through cancer. I believe that what I have worked out and tested on myself during medical treatment can also help other patients, so I wish to pass it on. In my opinion, microscopic images are the missing element in the narrative in oncology. I fill in this gap.

I’m looking for people in the world who want to meet their cancer through microscopic photography. I’m also looking for medical organizations that would like to incorporate microscopic photography of their patients’ cancers into their therapeutic work. I hope to make such contacts with the help of this interview.

Before your diagnosis, you had already felt a pull towards photographing cancer cells. How did your professional shift towards healthcare and the concept of Value-Based Healthcare influence your approach to this project?

The need to photograph cancer cells appeared in me long before my diagnosis. At that time I didn’t yet know that I would be photographing my own cancer. In early 2020 I took a career move towards healthcare. I went to the Netherlands to learn the Value Based Healthcare (VBHC) concept, which addresses the measurement of medical outcomes. The Dutch organization Value Based Healthcare Europe invited me to be their Ambassador in Poland. Since then, the vast majority of my professional projects have been related to healthcare.

Having a high aesthetic sensibility, from the very beginning I paid attention to the visual aspect and the messages that began to surround me in healthcare. I was surprised how few professionals in this field. Consider the fact that what we surround ourselves with in medical facilities, for example, and how we present various disease-related messages (including visually) has a huge impact on patients. Lack of awareness that this can make a difference to medical outcomes, prevention or the process of experiencing a disease is unfortunately common.

I believe that microscopic images of cancer can be an important part of the patient experience and add significant value to the perception of cancer. Both by patients and the wider social and cultural context.

What does microscope photography represent for you as a form of artistic expression? How do you see its role in transforming the visual narrative in healthcare and beyond?

While working on a project in oncology, I made the decision that I would like to focus on this specialization. Not only on the aspect of measuring medical outcomes, but also on how to bridge the gap that exists in the visual aspect. It seemed strange to me that we all know some kind of an image of covid, but no one knows what cancer cells look like.

In my opinion, microscopic photography of cancer is the missing link in the oncology narrative. I started looking for opportunities to photograph patients’ cancer cells.

Six months before my diagnosis, I started a postgraduate program in Psycho Oncology because I wished to deepen my knowledge and understand the perspective of cancer patients to know how I could help them. After a semester, I was diagnosed. I took pictures of my cancer. I won third place in the Nikon Small World contest. Life writes the script, and I opened my eyes in amazement and watched with curiosity as my story unfolded.

The microscope image is an integral part of healthcare. It’s just not available to everyone. The visual value I intend to share in the form of microscopic images to both patients and those working in healthcare can be a powerful tool in oncology and other medical conditions. Art is a value in itself. Used consciously in healthcare in the form of microscopic images, it has the potential to transform many narratives.

Can you describe your initial emotional and intellectual response upon seeing your cancer cells for the first time through the microscope? How did this encounter affect your perspective on your disease and your artistic expression?

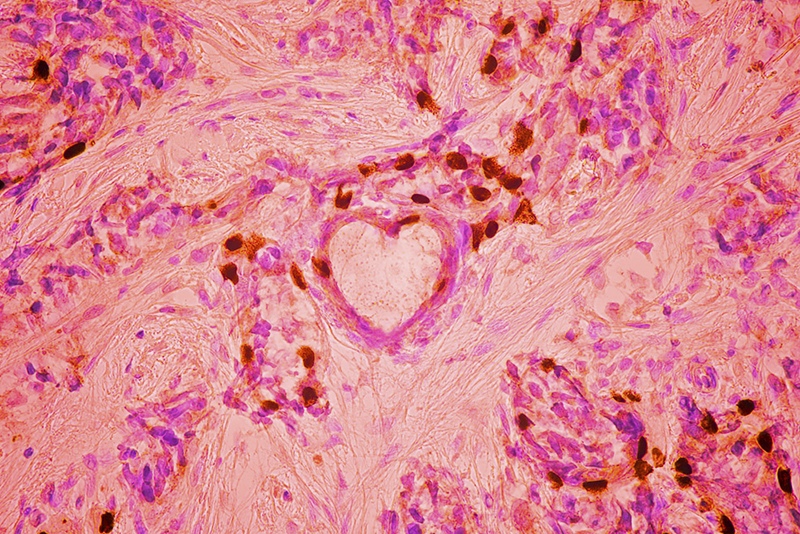

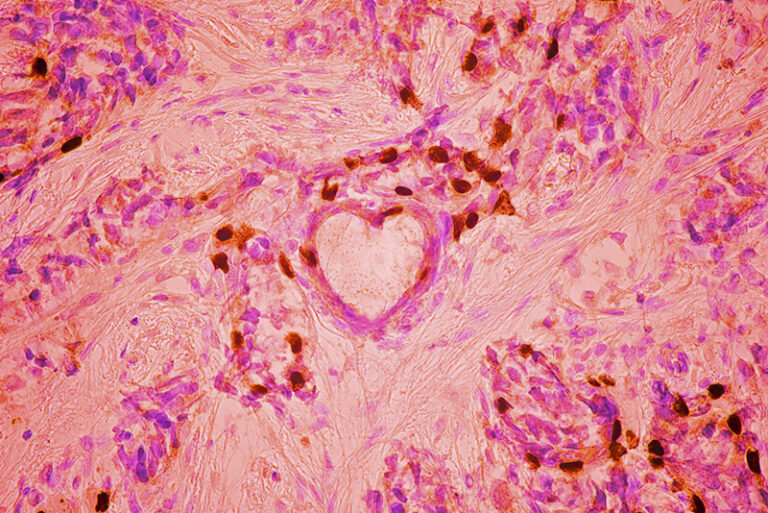

From the beginning of my disease, it was obvious to me that I need to face my cancer, but I was completely unaware of what I would see and how it would affect me. I remember my reaction when I first saw my cancer cells under the microscope. It was a burst of crying and amazement – “no, it’s impossible for something so beautiful to want to kill me!” Fantastic, abstract images created by my body in the process of carcinogenesis. The process of cancerogenesis that manifested itself in the form of a tumor impressed me from the very beginning. I saw “dancing” and “lost” cells which I could not take my eyes off. From the very beginning, the thought crossed my mind that I wanted to show it to the world. I also had the intention to convey to others that there was nothing to be afraid of, that my disease was a part of me, not a “stranger.” Then I stopped being afraid and focused on treatment. I realized that there was nothing to fight with and no one to fight against, because I would be fighting myself. I made the decision that I would treat myself with the greatest tenderness and love I knew how to give myself. The cells along with the tissue formed into a heart shape only completed my narrative.

Your work goes beyond traditional forms of art to expose the most intimate parts of the human body and condition. How did you navigate the balance between aesthetic appeal and the meaningful, often taboo, subjects you chose to explore?

I was definitely interested in addressing a taboo subject. At the very beginning, when I told those people around me that I was sick and what treatment I was going to get, I experienced social exclusion. Many people turned away from me. I went through a lot of changes in a very short time. The first two months of chemotherapy (out of five) were extremely difficult. Through social exclusion, I felt useless, because many people wrote me off. I didn’t know how to deal with it. After all, I was exactly the same person I was before the diagnosis. Yet everything changed overnight. I started chemotherapy in March 2023, and in April I decided to send photos of my cancer to the Nikon Small World microscope photography competition. Sending photos to the competition was a manifesto of life to me. I desired to be seen and accepted in the illness I was experiencing. Most people turned away from me, and I wished to manifest that I was alive and that I wanted to live. I was happy to be heard by the whole world. I took third place. For Poland, this is a return to the podium after 31 years. For me, it is a shake-up of reality. My intention was to show my cancer to the world the way I see it.

After submitting your cancer cell images to the Nikon Small World competition and achieving 3rd place, how has the public recognition affected your mission or message, especially in Poland where such recognition had not been achieved in 31 years?

Few people in Poland know that I won the Nikon Small World competition and that Poland returned to the podium after 31 years. Most people have never heard of this competition or understand its importance. Microscope photography in Poland is very niche.

On the other hand, my photography has reached many oncology patients in Poland. Now, after several months of observing how people react to my photo, I believe that people are more moved by the photo itself and my story, not by the place I took. Yet this is the greatest compliment for me – to be remembered by the picture, not by the place on the podium.

At the beginning of February this year I have started a project with a diagnostic company. This is a space to complete the visual aspect in oncology. We are starting a whole new narrative. With this collaboration, I assume that I will reach a wide audience. This short film, subtitled in English, can give a sense of the energy of the meeting.

Your views on not fighting against cancer but rather accepting it as part of oneself are profound. How has this philosophy influenced your treatment journey and your art?

Now I present cancer in a different version, the authentic one. It turns out that cancer cells do not have pincers, they are not monsters. You can even call them beautiful. What should we do now with such information? How should I fight my cancer cells, which are a part of me? How would I fight with myself? I didn’t know how.

Moreover, I believed from the very beginning that I didn’t have to fight In my opinion, fighting is stigmatizing. It divides us – patients into winners and losers. I believe that the war narrative weakens and does not support in the process. In a long treatment process like mine, I think it’s important to find your source of strength and motivation. It’s hard to be in the war narrative for several months of chemotherapy. I was very weak, during the first weeks of chemo, I could barely walk. I knew that only care and tenderness to myself would give me strength. This was the narrative I was in throughout treatment. Now that treatment is over, when I have had a 100% response to chemotherapy, I am post-surgery, mentally I feel even stronger than before treatment. Unfortunately, the war narrative is the dominant narrative in oncology. Many people in the world talk about different narratives, but officially no one has yet offered an alternative narrative. During my treatment, I started to work on it, and I believe I will soon share a new approach.

Could you explain the logistical and ethical process you went through to use your own cancer cells for your project? How accessible do you believe this approach is for others interested in exploring their conditions through art?

In Poland, the patient owns its medical tests, including biopsy tissue samples. Everyone has the right to take it from the place where they were diagnosed. You just have to go to the place where you were diagnosed, write an application and pick up the slides. Tissues from biopsies in the form of slides are stored for several years. Few people know about this. Few people take advantage of it.

Now I take pictures of other patients’ cancer. I explain to them where and how to collect the slides. They take the slides without any problem while informing the physicians that I will be taking pictures of their tissues. Apparently, physicians say it’s good that I’m doing this, that it’s important. It makes me happy that more and more people believe in what I want to do.

Based on my own experience, I believe that interacting with a picture of one’s own cancer could also be a valuable experience for other patients. However, not everyone may have the readiness to do so. I am also extremely grateful to cancer patients for their trust. I am touched when they hand me their biopsy and surgery slides and are willing to face their cancer eye to eye. It is an honor for me to accompany patients in this experience.

Lastly, what does art mean to you personally, and what role do you believe art plays in addressing societal challenges, such as the fear and stigma associated with diseases like cancer?

Art is a manifestation of life to me. It has always been my greatest support during difficult moments in life. The act of creation is linked to movement, and movement has the power to make things happen. If there is movement, there is also life, and life is movement.

By presenting authentic photographs of cancer in artistic perspective, I would like to reduce the level of fear in oncology. I would like to make people more familiar with the disease, which is democratic – it can happen to anyone. It’s also a wish for healthy people not to be afraid of oncological patients, so that they don’t turn away from us. It’s hard to go through an oncological disease alone. Today, cancer is recognized as a chronic disease. It is a part of life for millions of people around the world. Including those who are in remission. There is no avoiding this topic. Therefore, it is important to have a social transformation in the way we talk about cancer and how we perceive cancer patients. Behind the activities I am currently undertaking in oncology, there is also a need to heal myself. I would like to learn to live with the fear of relapse and not let that fear dominate my life. However, this will take time.

By intertwining the elements of art and science, Małgorzata Lisowska presents a story that shifts conventional views on health, illness, and human experience. Her efforts serve as a testament to the role of creative perseverance in shedding light on challenging moments, encouraging a perspective on health and illness that is rooted in beauty, comprehension, and optimism.