Gyotaku Art by Dwight Hwang

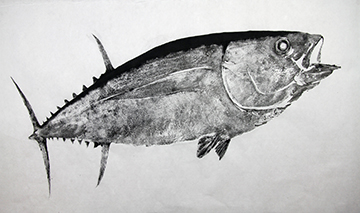

The origin of Gyotaku art can be traced back to the legend of a samurai lord or the birth of sushi in Japan. Regardless, beyond being a mystery, it is a fact that this style of nature printing has been a traditional way for Japanese fishermen to keep records of their catches since the mid-1800s. They ″printed″ the fish by brushing black ink on the fish and placing a sheet of rice paper on top of the fish so the form, style, and features of the fish could be represented on the paper. Because this process produces one-of-a-kind prints, it has been a reliable form of record-keeping and has been used continuously to the present time. Also, Gyotaku art has become a Japanese folk art form and the method of printing is currently used throughout the world.

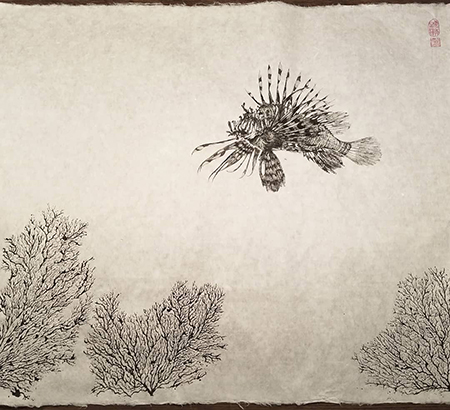

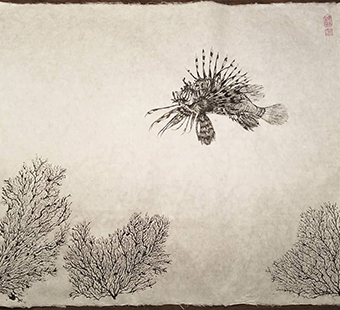

Dwight Hwang, a traditionalist of Japanese culture who lives in Orange County, California, has apprenticed himself in making Gyotaku prints for many years. Over time, he has transcended himself from the old way of recording the dead fish to his own unique style by giving ″life″ to these sea creatures. His imaginative mind, detailed brushstrokes plus vivid representations have created lively and artistic prints and assigned new meaning to the traditional Gyotaku prints. It is his combination of the presence-absence, black-white, subject-background, representation-manifestation, and life-death that make his prints stand out and sought after. Recently, I had the opportunity to interview him through email correspondence so readers can come to an understanding of his journey of reinventing the Gyotaku art style.

Q: Being a traditionalist of Japanese culture, please tell us your background growing up vis-a-vis how you fell in love with traditional art.

A: Traditional art has survived the ages for a reason. It′s classic and timeless, and with Japanese art, it′s usually deceptively simple which is one of the main reasons that I find myself so attracted to it.

Q: Please explain to us this unique Japanese cultural art style, ″Gyotaku″ — the purpose, process, required materials, and anything else.

A: There are two different origin stories that I′ve heard of in Japan. One is the highborn story, the other is lowborn.

The highborn story, which has records to prove parts of it, was that there was a samurai lord named Sakai in the early 1800s who enjoyed to fish. He would task his court calligraphers to document his catches. But one day there was a clever one who instead of writing the details of the catch, instead of brushed the sumi ink onto the surface of the fish, laid a sheet of paper on top of that to create a visual representation of the fish itself. Lord Sakai was taken by it and the practice continued.

The lowborn story coincides with the origin of sushi. When the capital was moved from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo), construction workers amassed. Requiring a nutritious but quick meal, sushi was developed. Often the common worker was illiterate and so instead of writing what the day′s catch was, the fish was printed so as to easily convey what was being offered.

Essentially, Gyotaku was considered a form of documentation or record keeping using the two materials that were most common at hand; sumi ink which was basically soot ground with water (the standard in calligraphy and sumi paintings and still is to this day). And washi which simply translates to ′Japanese Paper′ created from the pulp of mulberry bark.

Q: Please tell us how you transcended from the traditional to your own style.

A: We (as in me and my wife as we create these together in tandem), restrict ourselves to only using the same old world materials that were used when the art form originated; sumi ink and washi paper. However, we push ourselves to create pieces that are reminiscent of old, classical sumi paintings. We also place a lot of attention towards keeping the image proportionally correct as it is common for Gyotaku prints to look larger and wider than they should be. Lastly, we pride ourselves on developing ways to print our subjects at different angles and perspectives to create more depth and life. This isn′t typical of Gyotaku which is done from the flattest side of the fish to produce the standard ′side′ print. I like to think that it′s these three aspects that we will be known for.

Q: In your opinion, what are the most important elements in making this type of art?

A: To bring back life to what is dead. To instill respect and a love which may have been lost. To instill nostalgia to the viewer or to share an emotion that I would like for them to feel. Crisp details, perfect edges and other surface aesthetics are less of a priority to me as I′m much more interested in attaining a strong level of ′sonzaikan′ or presence within the piece.

Q: What inspires you when you decide to make a print — a fish, an image, their nature, or something else?

A: Before I ever thaw a fish or seek to attain one, I think of the motion and emotion that I wish to convey. Humans connect to human emotions, regardless of what the subject matter is.

Q: In the world of creative art, sticking with what you love can be challenging at times. Please share with us your journey as a traditional artist.

A: I′ve often been asked by my Gyotaku printing friends why I haven′t moved on to other inks, namely modern materials such as acrylic, oil-based inks, relief inks, etc. as traditional sumi can be difficult to control. It′s the original aesthetic that I first saw in Japanese tackle shops and at seafood shops which I fell in love with. And the difficulty in control results in very beautiful and organic spontaneity compared to more modern alternatives. Other inks and paints without a doubt have their benefits, but it′s the traditional calligraphy ink that suits me best.

Q: With your revised approaches, you have reinvented ″Gyotaku″ art, from documenting fish caught by the fishermen before the invention of the camera to fine art prints. Have traditional or modern paintings influenced your style of art?

A: I chose to remain as traditional as possible with both materials and aesthetics so I′m greatly influenced by classical Asian art of the times, specifically sumi paintings and woodblock prints.

Q: To me, your artwork has conveyed the philosophy of Taoism (Yin-and-Yang, black-and-white, figure-background, presence-absence). Do you try to convey this or another message in your art? If yes, could you share some of them?

A: Classical East Asian art is often greatly inspired by Taoism and its philosophies of balance, and so I am also a student of these sorts of aesthetics. By creating a scene via Gyotaku by expressing presence and absence, I think it is in this way that this old folk art can transcend its fisherman origins. There can be such beauty, power and calm when focusing on the simple.

Q: At what stage do you become satisfied with your art and feel it is ″done″ — the details, visual effect, spirit, or something else?

A: Most important to me is conveying presence. That the image on paper is indeed animated, alive and/or expressing an undeniable emotion. Other times, it′s simply a self-challenge where I hope that others will view it and wonder, ″How did they do that?″.

When I judge a piece, it shouldn′t appear labored or forced. If it looks as though my process was frustrating and difficult as opposed to organic and fluid, it′ll be recycled and used as scratch paper for the next attempt.

Q: Where can people view your art in person? What are the things a collector should pay attention to since your art is on very thin sheets of rice paper?

A: There are several places of business that regularly display our artwork, and there are a steady number of museum exhibitions and live demonstrations scheduled throughout the year, all around the country. People are also more than welcome to come and visit me at my home studio and view our Gyotaku in person.

Regarding the paper, nearly all of our original pieces (and many of our reproductions) are on handmade papers imported from artisans in Japan and Korea. The papers are thin and the Gyotaku process will inherently exhibit natural waves within it. This is normal. However, when placed up against a matte or frame, the paper will wrinkle drastically. It′s best to float these original pieces inside a shadowbox frame so that it sits inside in its natural state giving it the appearance of an artifact. If the owner wishes to place it inside a conventional frame with matting, then we also offer a service to wet mount/flatten the piece that will remove all the waves & wrinkles, producing a perfectly smooth piece. I personally prefer untreated Gyotaku, but that′s just because that is how I had originally seen them during my years in Japan.

We thank Dwight for spending his time taking us back in time to understand an ancient Japanese folk art and how he has transformed this folk art to a style of his own. We truly admire his endeavors and faithfully keeping to the old and reinventing the new. We wish him great success.

Dwight′s Website