Inside of a drop of water is a mysterious world in miniature, alien to most people. It contains much of the information that might provide the answers to the origin of life and environmental sustainability. To start with, a drop of water contains thousands of microorganisms. What are they, what do they look like, and what roles do they play in the ecological system? Trying to answer these questions, scientists have delved into this puzzling and yet complex world for many decades. Based on their research, some of these organisms (e.g., cyanobacteria) came into existence approximately 3.5 billion years ago and are responsible for producing more than half of all the oxygen that all life forms rely on today. Depending on the source, these organisms vary from single-cell and colonial microorganisms, such as Dinobryon, which are natural water purifiers, to small animal species such as Hydra which has extremely long lifespans. They come in a wide variety of spectacular patterns and shapes that are truly beautiful to behold and naturally artistic. The total number of such organisms is vast.

Swedish micrographist, Dr. Håkan Kvarnström, has turned his passion for microorganisms into a series of captivating images recording the intricate beauty of these tiny organisms found in a drop of water under his microscope. Over the years, his aesthetic approaches have won him many international awards including a recent photo titled ″Bouquet de fleurs″ won the 2018 UK Royal Society of Biology Photographer of the Year Shortlist. Utterly astounded by his images, I recently contacted Dr. Kvarnström for an interview. From the Q&A below, Dr. Kvarnström describes in detail the world that fascinates him and how he has forged a bridge between science and the arts for the public to appreciate.

Q: Please explain to us what a photomicrograph is, and what got you interested in this? What is your goal in the pursuit of photomicrography?

A: A photomicrograph (or micrograph) is a photograph of a small object taken through a microscope. I have always been interested in science and technology, including the instruments used to explore space and microscopic worlds. This is how I got into microscopes and the fascinating worlds they reveal. The microscopic world is like space, an endless world ready to be explored. Almost every time I look through a water sample with a microscope, I find something new and exciting to study. The exploration of these worlds and the excitement of discovering microscopic lifeforms is what drives me. The intricate beauty of nature′s design and the delicate structures of tiny life forms never ceases to amaze me. It makes me think about life on earth and how incredible pervasive microbes are. The total biomass of microscopic protist and bacteria outweigh animals and humans on earth by 35 times. Also, more than half of the world′s oxygen is produced via phytoplankton photosynthesis. Yet, they are invisible to the naked eye.

Q: Your images are really astounding and informative. Which subjects interest you the most and why?

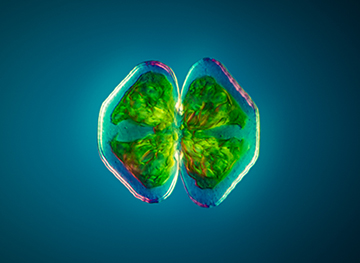

A: My work is primarily focused on life living in the water. Life on earth once started in water environments, and the variety and diversity of microscopic life living under the surface are mind-boggling. A favorite subject is blue-green algae, aka cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria have been around for over 3.5 billion years and still serve a significant role in ecology today. The cyanobacteria have been crucial in shaping the course of evolution and ecological change throughout the earth′s history. The oxygen-rich atmosphere that we depend on was generated by cyanobacteria billions of years ago. Cyanobacteria are still producing as much as 25-30% of the earth′s oxygen. Cyanobacteria were one of the first life forms that developed photosynthesis and learned how to make food using sunlight. The chloroplast with which plants make food for themselves is originating from a cyanobacterium living within the plant′s cells.

Q: How do you decide which sample to collect — from a research report, curiosity or something else?

A: My main driver is curiosity and the excitement of making the invisible visible and available for everyone to see and explore. It is like an obsession. Every drop of water may contain a surprise. Everywhere I look, I see potential samples to study. I might be a lake, a small water pond in a park, a rock covered with lichen, an insect or larva, flowers, and plants. I can browse through pond water drop by drop for hours searching for life forms to explore. I almost always find something interesting to explore, and that is what drives me. It is fascinating that so many microscopic species can be found just by sampling a local pond or lake. You do not have to travel to exotic places far away to explore the beauty of nature. It is right next to you.

Q: When you look at a sample under the microscope, what aspect of it are you most interested in: its behavior, physical characteristics, aesthetics, something else?

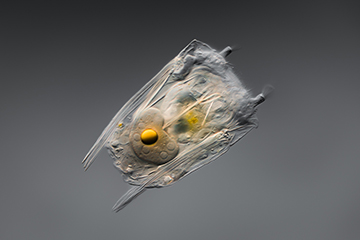

A: All of the above! Some subjects show spectacular swimming behavior like rotifers and dinoflagellates. They are gliding elegantly through the water sample with extreme precision. Euglena and Stentor are like micro shapeshifters that can change shape from a ball to a long string in a matter of seconds. At the same time, they are both beautiful with their bright green bodies. The micro world is very different in many ways. A small animal species, Hydra, is believed to have eternal life. Recent research suggests that hydras do not undergo aging, and, hence, are biologically immortal. They can, of course, still be eaten or killed by predators or other means. However, due to their ability to move between stages of life in response to stress and damage means that they could live forever. At least in theory. When a Hydra is cut in half, each half will regenerate and form a small Hydra; the ″head″ will regenerate a ″foot″ and the ″foot″ will regenerate a ″head″. If the Hydra is sliced into many segments, then the middle slices will form both a ″head″ and a ″foot″. I find this truly amazing. Perhaps a better understanding of these mechanisms among Hydra is the key to eternal life for humans?

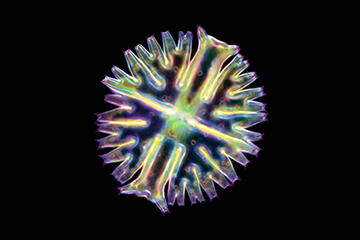

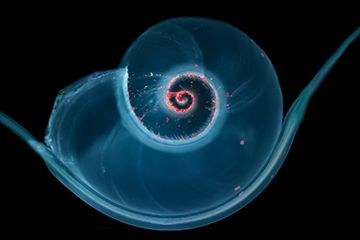

The artistic side is equally interesting to explore. Nature′s design at the micro-level is full of art, from the endless variety of symmetric patterns of diatoms to the golden ratio of the spiral of seashells. Sometimes the beautiful appearance of a subject may be enough, but in most cases, when you study the subjects, you find that they tell incredible stories that complement the image. The late photojournalist Ernst Haas once said; ″Photography is a bridge between science and art. It brings to science what it needs most, the artistic sense, and to art the proof that nothing can be imagined which cannot be matched in the counterpoints of nature″. My photography aims to explore the intersection between art and science.

Q: ″To see a World in a Grain of Sand″ as William Blake, an English poet once wrote. In your case, have you also seen a world in a specimen? If yes, please describe the world you have seen.

A: What I find so fascinating is that patterns in the design of nature repeats itself. You find patterns that are fractions of a millimeter in size and invisible to the naked eye, which you also can find in galaxies spanning thousands of light-years in size. Micro mollusks are small invertebrates that can be smaller than 1 mm in size. The shell of the mollusk typically have a beautiful spiral shape and often have bacteria and microalgae growing in the grooves of the spiral. When lit with blue and ultraviolet light, the bacteria and algae start to radiate in red and orange and resemble little shining micro stars in a micro galaxy. Independent of size, the world as we know it, have found the spiral to be a successful and recurring design.

Q: Please share with us some of your most unforgettable experiences in your pursuit of photomicrography.

A: I do not have a degree in biology, and I explore the microbial world with great admiration for its diversity and incomprehensive beauty. Over the years, I have learned to identify many of the species I see, but it is always a great experience every time I find something that I have never seen before. Sometimes I can spend hours trying to understand what I see in the microscope′s eyepieces. Fortunately, there is excellent literature available to help identification.

Q: What do you do when you spot a mutation in a cell? Do you track the mutation?

A: I have never spotted a mutation as far as I know, and I think it would be difficult to draw a conclusion whether a cell was mutated or not using a light microscope only. I often find deformed cells, which is common when species, like microalgae, is living and reproducing under harsh conditions. For example, when the temperature, level of nutrients, or other living conditions may be less than optimal for normal cell division.

Q: Do you work with other scientists and share your images with them? If yes, which field of scientists are most interested in the images you produce?

A: Yes, I do. I have met many scientists through my Instagram account. Microbiologists, marine biologists, but also scientists and professors from other fields show an interest in my work. Micrographs are useful in many disciplines for several applications. In most scientific fields, the interest in micrographs is purely scientific. The aesthetics usually is of less importance. In research, they are often used to highlight certain features or characteristics of a specimen, for example, to prove or disprove research findings and theorems or in clinical work to diagnose a disease. The beauty of the image is secondary, and no attempts are made to enhance its visual appearance. They are still good or excellent micrographs because they serve their purpose. The goal of my photography is to show the beauty of the microscopic world. I see the microbes I find as my models, and I try to figure out how I can portray them in the best possible, and visually pleasing, way. I spend a lot of time cleaning specimens, isolating individual cells, positioning them in the right environment, and sometimes use stains to highlight certain features of a subject. Not so different from a photographer using makeup artists and models. As with most skills, the more you practice, the more you learn how to handle different microbes and how you best image them. In my opinion, a common mistake is to spend too little time on planning and preparing a photoshoot resulting in a snapshot of some random subject rather than a good micrograph.

Q: How small of an image is your equipment capable of taking a photo? Can you take photos of DNA strings?

A: I exclusively use light microscopes for my micrographs. Per definition, a light microscope′s resolution, or resolving power, is limited by the wavelength of visible light. Under perfect conditions, I can resolve details as small as around 200 nanometers (0.002 mm). This level of detail makes the shape of bacteria visible, but it is not possible to resolve any details. DNA strings are way too small for a light microscope. It can generally resolve the cell nucleus (where the DNA is), but not the strings itself.

Q: In your opinion, what are the major challenges these microbes are facing in our current environment?

A: Microbes will probably outlive all other life forms on earth. Many of them have developed amazing abilities to survive and reproduce, even under harsh conditions. Rotifers are the smallest animals on earth. Some as small as 40 micrometers in size. Rotifers have existed for at least 35 million years as they have been identified in fossilized amber. Under tough conditions (e.g., drought), rotifers can go into a desiccated state as a cyst or egg that can survive for decades without any signs of aging. The wind can carry the cysts and allow the rotifer to spread and escape harmful conditions. Once it finds water, the rotifers come back to life.

I think a more interesting question is what challenges other life forms, including humans, are facing if we see a decline in microscopic life (e.g., phytoplankton). For example, a temperature rise of the oceans of the world may have a massive impact on the microbes and plankton living underwater. According to recent research by NASA, the world′s oceans have seen significant declines in certain types of microscopic life at the base of the marine food chain. The study looked at long-term phytoplankton community trends based on a model-driven by satellite data. Diatoms, which are the most abundant type of phytoplankton algae, have declined more than 1 percent per year from 1998 to 2012 globally. When phytoplankton dies, it sinks to the ocean floor bringing the carbon it has absorbed from the atmosphere. A decline of the population may decrease the amount of carbon dioxide drawn out of the atmosphere and then transferred to the deep ocean for long-term storage. Whether this decline is caused by natural variation or climate change still remains unclear, but the research provide a first insight into trends in phytoplankton distribution and how changes in the conditions over the last 15 years may have affected them.

We are very grateful for Dr. Kvarnström taking the time to let us know about the world in a drop of water and the amazing images he has captured. We look forward to seeing more wonderful images captured by Dr. Kvarnström from here on. For more information, his short bio and a link to his Instagram, Flickr and website are listed below.

SHORT BIO

I have always been curious about the invisible. As a scientist by heart and education, I am inspired by looking beyond what you can see with the naked eye, whether it is distant stars or microscopic life forms. My work focuses on unveiling the beautiful treasures of nature. A place where art and science meet. Photography brings an artistic sense to science and through my photographs, I aim to spark curiosity and create awareness of the ecological significance of microscopic life forms. My images are all about small life forms telling grand stories. In 2014, my interest in photography accelerated as I started taking pictures through microscopes. I was amazed by the diversity, complexity, and intricate beauty I found wherever I looked. The amazing thing is, it is so close to you and yet so hard to see and experience. I hope my photographs will inspire you with that same sense of spectacular beauty that surrounds us!

Instagram: www.instagram.com/micromundusphotography

Flickr: flickr.com/micromundus

Website: https://hakankvarnstrom.com/