Stargazer Extraordinaire: Gary Lopez's Fusion of Art and Astrophotography

The vast universe is like a splendid and colorful painting, filled with endless wonders and mysteries. In this realm of dazzling starlight, Gary Lopez stands as a pioneering explorer. With unique ingenuity, he elevates astrophotography from mere scientific recording to breathtaking works of art. Through each of his creations, Lopez invites us to jointly explore the hidden marvels of the cosmos, to reassess our understanding of the vast space, and to spark our boundless imagination of the universe’s mysteries. His works are not just records of celestial bodies but also interpretations of the human spirit of exploration, allowing us to feel a profound connection between ourselves and the universe as we admire them.

Lopez’s journey is as fascinating as his photographs. Formerly a collaborator with the legendary Jacques Cousteau, he transitioned from exploring ocean depths to celestial heights. Armed with a Ph.D. in Marine Biology and decades of documentary filmmaking experience, he blends scientific rigor with artistic vision to create breathtaking images of deep space. His work is not just a hobby but a culmination of lifelong passions, pushing the boundaries of both science and art.

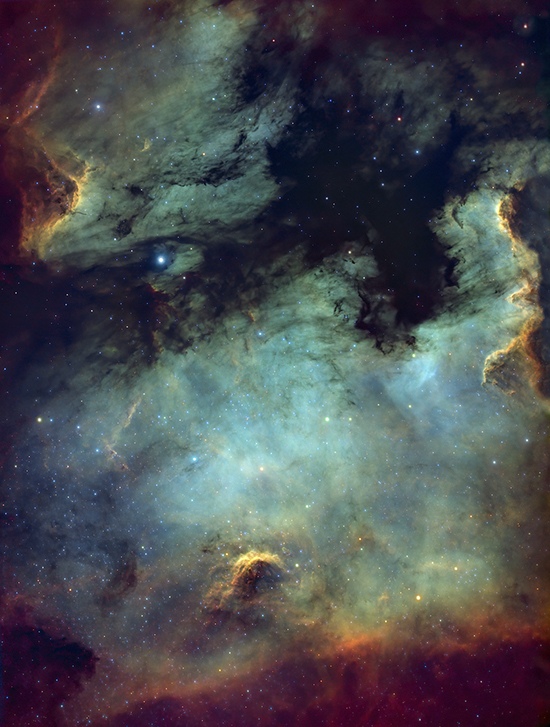

Inspired by iconic images like the Hubble Space Telescope photograph, “Pillars of Creation,” Lopez mastered advanced techniques to capture deep-space objects. Utilizing specialized filters that pierce through light pollution, he reveals the faint glow of ionized gases in emission nebulae—vast clouds invisible to the naked eye. His meticulous process involves planning, long exposures, and weeks of refinement, often collaborating with his wife, abstract painter Monica Johnson, to evoke profound emotional impact.

Lopez’s dedication has earned him significant recognition, including winning the Nature category in the International Photography Awards two years in a row. Beyond personal achievements, he envisions astrophotography as a unifying force, fostering global connections by allowing people worldwide to share in the beauty of the same sky. We recently had the honor of delving into his journey, creative process, and hopes for the future of astrophotography. We hope you enjoy this insightful conversation.

Q: What inspired you to pursue astrophotography as a form of fine art, and how do you integrate classical photography techniques into capturing the cosmos?

A: I’ve been interested in astronomy and astrophotography since I was a kid. When I was 12, I bought a telescope and even made a camera. I took some really bad photographs, but I was inspired by the ability to visualize these places and things in space. I found it mysterious, dramatic, and exciting.

Fast forward to the 1990s when the first images from the Hubble Space Telescope came back. In 1995, there was one called the “Pillars of Creation,” which was stunningly beautiful and dramatic. I was blown away. I realized then that you could potentially create something truly artistic with this technology, but it took another 20 years for digital camera and filter technology to advance to a point where you could do that from your backyard.

Around 2015, the technology had progressed enough that I could dive in. I built an observatory in my backyard, gathered the necessary equipment, and began exploring astrophotography. It wasn’t long before I realized there are so many subjective decisions you make when creating a photograph that you really are making art. It’s not purely objective or scientific; you’re making choices based on your tastes and intentions. And that’s when everything clicked for me.

Q: What elements contribute to your subjectiveness when capturing something as vast and abstract as the night sky?

A: Certainly, composition is the starting point. Deciding what’s in the frame and what’s left out involves all the fundamental elements that go into any kind of fine art photography—the color palette, textures, lines—there are many factors at play. As you’re creating an image, all of these come into consideration.

For some people, particularly scientists, the goal is to center the subject to gather the most data. But when you’re aiming to move someone emotionally, those artistic elements become crucial. The first time I realized this was possible was with an image called “Flaming Star.” It’s a turbulent nebula with one brand-new, bright blue star. As I worked on the image, I realized I wanted to enhance the sense of depth.

If you’re familiar with macro photography, you know that when you take a close-up picture of a flower, the subject is in perfect focus while the background is out of focus due to the depth of field—this is called the bokeh effect. I created a kind of mask that allowed me to apply a bokeh effect to this image. The result was that it came forward with great depth and texture, in a way that isn’t naturally possible—you can’t have depth of field over 3,000 light-years! So you have to create this effect. At that point, I realized, “Oh yeah, I can really make some interesting art.”

Technology has also advanced. For a long time, people were using regular DSLRs, but the exposures needed were very long, and so much heat built up in the sensor that you got thermal noise very quickly. About a decade ago, commercially available cameras for astronomy began to include electronic cooling. Now, when I take long exposures, I keep the camera at around -15°C to ensure there’s no thermal noise. Knowing that, the technology has improved significantly.

Q: How far away are the objects you photograph?

A: The distances we’re dealing with are measured in light-years—the distance light travels in a year, about 6 trillion miles. But for me, the crucial factor isn’t the distance itself; it’s the brightness or luminosity of the object. You can have objects that are relatively close but very dim, and others that are much farther away yet extremely bright.

Since I’m creating art, my primary interest lies in emission nebulae. These are enormous clouds of gas and dust that emit a faint glow because the energy from nearby stars ionizes elements like hydrogen, sulfur, and oxygen. This glow is so faint that you can’t see it with the naked eye, but with long exposures—totaling 15, 20, 30, or even 40 hours—you can capture it.

So, it really comes down to what I can use to compose an image that achieves the emotional impact and artistic intention I’m striving for.

Q: Please tell us about the James Webb Telescope. It has expanded our knowledge about the sky a lot more.

A: The James Webb Space Telescope is allowing us to see farther and in more detail than ever before. While it’s certainly changing some aspects of our understanding, what’s important is how it works compared to previous telescopes like Hubble or even my own work.

The Hubble Telescope and the astrophotography I do utilize visible spectrum light. This light travels through space but can be interrupted by dust and other cosmic materials due to its shorter wavelengths. Over long distances, this interference can limit what we can see.

The James Webb Telescope, on the other hand, observes in the infrared spectrum, which has much longer wavelengths. Infrared light can travel further with less interruption because it’s less affected by dust and gas. This allows the Webb Telescope to see more detail in certain phenomena and to look deeper into the universe than was previously possible.

By capturing infrared light, James Webb is revealing aspects of the cosmos that were hidden to us before, enabling us to explore the universe in ways we couldn’t with visible light alone.

Q: Your images have received significant recognition in international fine art photography competitions. Can you share the story behind one of your award-winning photographs and what made it stand out?

A: There are a number of competitions for astrophotography, but I was interested in establishing astrophotography within classic fine art competitions. I entered an image entitled “Islands in a Radiant Sea” in the 2020 International Photography Awards (IPA), and to my amazement, it won the Nature category. In 2021, I entered another image, “Scarlet Lightning,” and again it won. At that point, it became clear that astrophotography had come of age as a category of fine art photography.

I think the reason “Islands in a Radiant Sea” won the 2020 IPA was because it might have been the first deep space image to be entered in the competition. People had entered astrophotographs before, but they were mostly pictures of the Milky Way on the horizon and similar subjects. But I was showcasing deep space objects. As for galleries, deep space astrophotography is still not widely accepted as a form of fine art photography. As far as I know, I am one of the only astrophotographers whose work represented by commercial art galleries, at least in the U.S.

Q: In your work, you mention using framing, color, movement, depth, and texture to evoke emotional impact. Astrophotography often requires long exposures and careful planning. How do you balance these elements when capturing something as vast and abstract as the night sky, and can you walk us through your creative process from selecting a location to capturing the final image?

A: For most of my images, I start with a basic compositional plan. I do extensive research to figure out what I’m going to shoot and how it will fit within the frame. I have an initial idea of how I intend to compose the image. However, as I begin collecting exposures, almost without exception, something new appears that I didn’t expect. If this new element resonates with me—especially if it has emotional impact—I dive deeper into it, following where the data and exposures take me.

Balancing elements like framing, color, movement, depth, and texture is a dynamic process. I believe the emotional impact of an image starts with the artist—what they feel when they see the image. If you feel it deeply—if it moves you emotionally—you know you’re onto something. You move in that direction and hope that others will feel the same way.

An important aspect of my creative process involves the use of specialized telescope filters that came onto the market about ten years ago. These filters block all emissions except within a narrow three-nanometer range. This allows me to look right through light pollution and capture only the specific spectra—the light emitted by individual glowing gases. It’s a huge advantage for me creatively, as it enables me to capture images with greater clarity and detail. It also allows me to create these images right here in Monterey from my backyard. If you’re patient—you have to be a little crazy and patient—you can achieve this.

I spend days or even weeks tweaking the composition, colors, and textures to unleash the power, beauty, or drama of the image. I often share works-in-progress with my wife, Monica Johnson, who is an abstract painter, to get her feedback. Sometimes I’ll set a piece aside for a few days to let my mind reset before re-engaging with it.

I also make dozens of test prints and observe them in different lighting conditions—morning light, midday, warm end-of-day light—to see how the image responds. This helps me refine the artwork until it aligns with my artistic vision. Ultimately, it’s about following where the image leads me and trusting my emotional response to guide the process.

Q: You have an impressive background in filmmaking, including producing documentaries for Jacques Cousteau and his son. How has your experience in filmmaking influenced your approach to astrophotography?

A: In documentary filmmaking, I learned the importance of telling a basic story using just visuals—without relying on narration or music. I apply the same approach to my photography. I strive to create images that either tell a story or elicit one from the viewer. What’s fascinating to me is how the “story” can differ greatly from person to person. Since many of my images are of amorphous nebulae, what people “see” often reflects their own background or frame of mind.

Q: Your film Voyage to Kure inspired President George W. Bush to establish the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument. As both a filmmaker and photographer, how do you see the relationship between art, science, and environmental conservation, and how do you decide which medium best conveys the story or emotion you want to share?

A: The ability to use art to influence public opinion and perception is something I learned from Captain Cousteau, who famously said, “People protect what they love.” In our work together, we strived to create films that gave people a sense of familiarity and evoked compassion. The intention was to build a relationship between the audience and the animals or places we showcased, fostering a vested interest in their well-being. This approach resulted in a concerned, informed public and spurred movements to protect and conserve the environment.

When deciding which medium best conveys the story or emotion I want to share, I consider several factors. First is the nature of the story itself. A documentary film can guide the viewer through deeper development and complexity than a photograph or photo series might. The second consideration is the audience I aim to reach. In the case of supporting environmental conservation—as with the Cousteau work—documentary films broadcast on television are effective because they can impact public opinion and, consequently, policy.

In contrast, with my astrophotography, my goal is to give the viewer an experience that connects them with the universe in a personal way, allowing them to see themselves in a different context. A photograph can accomplish that by capturing a moment or scene that evokes a profound emotional response. So, the choice of medium hinges on the story’s demands and the most effective way to engage the intended audience.

Art serves as a bridge between science and the public, translating complex concepts into relatable experiences. Whether through filmmaking or photography, my aim is to use art to foster understanding and inspire action toward environmental conservation.

Q: With your Ph.D. in Marine Biology and extensive scientific background, how has your scientific knowledge informed your approach to both filmmaking and astrophotography? How do you navigate the balance between technical precision and creative expression in your work, and how do you see the role of science in deepening our emotional understanding of the cosmos?

A: Knowing the science helps me identify and understand topics that have true impact, allowing me to flesh out the core truths. Whether I’m making a film or creating a photograph, I use these mediums as vehicles to bring those truths to the public in a way that enhances understanding and perspective.

Balancing technical precision and creative expression requires careful navigation. My goal in making a film or photograph is to present what is real in a manner that has emotional impact. In astrophotography, for example, artistic interpretation is expressed through composition, color palette, the printing process, and the choice of media. What I never do is alter what is genuinely there—I don’t add or remove structures. However, I do adjust exposure to highlight or reduce the appearance of certain parts of an image, a very common technique in photography.

I’ve engaged in discussions with other astrophotographers who have strong scientific backgrounds regarding the “manipulation” of astroimages. There’s a concern that improper manipulation can result in an image that isn’t “real.” For me, I never alter the raw data (exposures) used in an astroimage. Instead, I use color, exposure, and other techniques to create an artistically impactful image. It’s similar to taking a page full of measurements and displaying them in a graph or table—the data remain the same, but the display allows the viewer to see and understand aspects that are hidden in the raw numbers.

I believe that science interpreted through art is the most powerful vehicle for creating an emotional understanding of the cosmos. Scientists grasp the scales of time and space through mathematics and theory. For everyone else, art can take the complexity of those scientific realities and offer a portal to see and feel the cosmos, helping us gain a real perspective on our place in the universe. By bridging the scientific and the emotional, we can connect viewers to the universe in a profound and personal way.

Q: What challenges have you faced in transitioning between your roles as a scientist, filmmaker, and fine art photographer, and how have you overcome them?

A: Creating a career that encompasses all of my interests has certainly been challenging. There was no obvious employment path that combined science, filmmaking, and fine art photography, so I had to invent one myself. I founded a company called Archipelago, which produced and developed films, videos, software, and books—primarily on science topics. This was particularly challenging because I don’t have a business background.

Another challenge has been finding colleagues who are on the same journey. To my science colleagues, I’m the artist or business guy. To my artist colleagues, I’m the science or business guy. And to my business colleagues, I’m the professor or art guy. Navigating these different perceptions has been complex, but it has also enriched my experience by allowing me to bridge diverse fields.

Q: What upcoming projects or themes are you excited to explore in your astrophotography or filmmaking?

A: My main artistic focus these days is establishing astrophotography as a recognized fine art form. My work is represented by two galleries: Gallery Sur in Carmel, CA, and Waterfall Gallery in New York City. I recently had my work featured in an exhibit at the Monterey Museum of Art. Moving forward, I’d like to participate in more museum exhibits and engage in public art projects. I’m excited about the potential to bring astrophotography to a wider audience and to explore new themes that connect people with the universe.

Q: Looking back at your career, what moments or achievements stand out to you as the most defining?

A: There are several milestones that have been particularly defining for me, many of which not only validated my work but also opened doors to new opportunities. Being accepted into the Ph.D. program at Scripps Institution of Oceanography was a significant achievement. Writing my film script for Encyclopedia Britannica Films and collaborating with filmmaker Bert Van Bork were pivotal moments. Meeting and working with some of my heroes—including Stephen Jay Gould, Jacques Cousteau, and Bill Gates—has been incredibly rewarding. I’ve been very fortunate to have had the chance to pursue my interests and passions.

Failures have also played an important role in shaping my career. For example, I was rejected by half a dozen colleges and universities when I sought a professorial position. I simply wasn’t the right fit. That failure forced me to rethink and reinvent my path forward. Without that setback, I likely wouldn’t have had the career I enjoy today.

Q: If you could give advice to aspiring astrophotographers or filmmakers, what would it be?

A: I would offer the same advice I’ve given my children: It’s crucial to pursue an occupation you love because you’ll be doing it every day. For those passionate about the arts, there’s always the challenge of “making a living.” This reality is why many artists become salespeople or art faculty in schools. However, with platforms like YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and other social media outlets, more artists than ever before can monetize their work.

Even if you’re able to make the finances work through these avenues, it’s important to find an occupation that pays the bills while giving you the time and resources to pursue your art. For many of us, making art is like breathing—you simply can’t survive without it.

Q: How do you envision the future of astrophotography, particularly as it intersects with environmental conservation and scientific communication?

A: I envision that amateur astrophotography will continue to grow worldwide as the cost of equipment decreases. While this growth will certainly impact scientific communication to some degree, I believe it will have an even greater effect on societal communications. We are all observing and photographing the same sky.

Astrophotography allows groups of people in different time zones, countries, and continents to work together to create images. This common experience fosters a bond and open communication that transcends politics, religion, and culture.

Through his pioneering work, Gary Lopez demonstrates how astrophotography serves as a unifying force, bridging gaps between science, art, and society. As this field becomes more accessible, it has the potential to foster global connections and inspire collective stewardship of our shared universe. By capturing the beauty of the cosmos, we not only expand our understanding but also cultivate a sense of unity that transcends borders and cultures.

Gary’s art is represented by:

Gallery Sur

Carmel, CA

Waterfall Mansion and Gallery

New York City, NY