Starving Cancer: How Engineered Fat Cells Could Revolutionize Treatment

Scientists at UC San Francisco have developed a groundbreaking cancer treatment that transforms ordinary fat cells into cancer-fighting agents. This innovative approach could one day provide patients with a less toxic alternative to conventional therapies, while opening new doors for treating metabolic disorders.

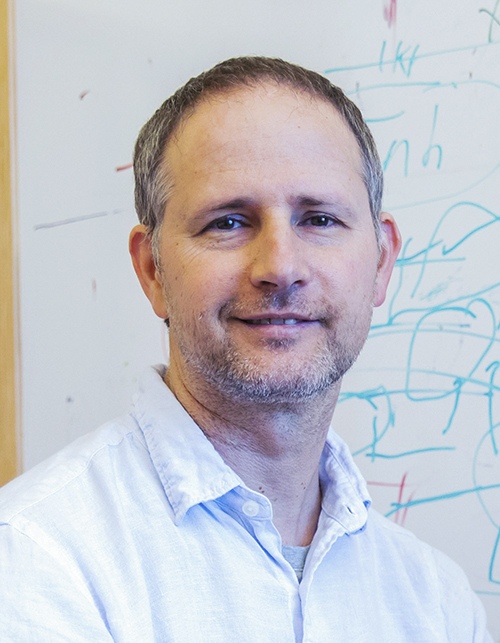

This research, led by Nadav Ahituv, PhD, director of the UCSF Institute for Human Genetics and professor in the Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, was published Feb. 4 in Nature Biotechnology. Dr. Ahituv’s team used CRISPR gene-editing technology to convert white fat cells—the kind that stores excess calories—into energy-hungry beige fat cells. When implanted near tumors in mice, these modified cells outcompeted cancer cells for vital nutrients, effectively starving the tumors and suppressing their growth.

“We were inspired by a 2022 Nature study from Yihai Cao’s lab in Sweden’s Karolinska Institute showing that cold exposure, which naturally activates brown fat, could suppress cancer,” explains Dr. Ahituv. “But putting frail cancer patients in cold rooms isn’t practical, and brown fat activity decreases with age, thus not being as helpful for older cancer patients.”

Instead, the UCSF team developed a more direct approach: extracting white fat cells, reprogramming them to burn energy like brown fat, and reimplanting them—a process that borrows techniques from plastic surgery. “We already routinely remove fat cells with liposuction and put them back via plastic surgery,” Dr. Ahituv adds, highlighting the feasibility of their approach.

From Obesity Treatment to Cancer Therapy

The journey to this discovery began with obesity research. The team had already developed ways to implant modified fat cells to prevent weight gain in mice on high-fat diets when they recognized the potential applications in cancer treatment.

Their first experiment was surprisingly effective. Using a simple model where cancer cells grew in a dish below modified fat cells, they observed significant tumor suppression across multiple cancer types, including breast, prostate, pancreatic, and colon cancers.

“The results were so dramatic we initially thought we’d made an experimental error,” Dr. Ahituv recalls. “We had to repeat it several times to believe it.”

A Matter of Metabolic Competition

The core mechanism is straightforward: cancer cells require substantial nutrients to fuel their rapid growth. By introducing cells that aggressively consume those same resources, the engineered fat cells create a competitive environment where cancer cells are effectively starved.

The team confirmed this by conducting experiments with mice on high-nutrient diets, where the cancer-suppressing effects were diminished—proving that resource competition is crucial to the therapy’s success.

Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that these modified cells don’t need to be placed directly next to tumors to be effective. In genetic breast cancer mouse models, cells implanted away from the tumor site still significantly reduced tumor growth—a finding that could simplify treatment for hard-to-reach cancers.

“This was particularly exciting for us,” notes Dr. Ahituv. “For pancreatic cancer, we initially performed challenging surgery to place cells adjacent to the pancreas. When we discovered distant placement worked just as well in breast cancer models, it opened up possibilities for treating cancers in difficult-to-access locations, like glioblastoma.”

Beyond Basic Competition

While nutrient competition appears to be the primary mechanism, Dr. Ahituv believes other beneficial effects may be at work. “We observed reduced insulin levels in these mice, suggesting the cells may be improving overall metabolic health,” he notes.

The team has also demonstrated remarkable adaptability in their approach. When they encountered pancreatic cancer cells that switched to using uridine instead of glucose, they simply reprogrammed fat cells to consume uridine by upregulating a different gene (UPP1).

“This highlights one of our key advantages—we can customize the metabolic profile of our cells to target whatever pathway the cancer is using,” Dr. Ahituv explains. “It creates the possibility of an ‘arms race’ where we continually adapt our approach as the cancer evolves.”

Currently, their approach suppresses rather than eliminates cancer cells completely. “We saw reduced proliferation, decreased blood vessel formation, and other cancer-suppressing effects,” says Dr. Ahituv, “but not complete cancer cell death in all cases.” The team is now working to enhance effectiveness by targeting multiple genes simultaneously—potentially achieving true cancer cell killing in future iterations.

Engineering Approaches and CRISPR Technology

While CRISPR gene activation (CRISPRa) was central to the team’s published research, Dr. Ahituv emphasizes their flexibility in engineering approaches. “We’ve also successfully experimented with simply inserting cDNA to express more of the target gene, which works very well and might actually be an easier pathway to clinical implementation,” he explains.

The advantage of CRISPRa is its scalability for future work. “We’re now working on upregulating multiple genes simultaneously, and CRISPRa makes it much easier to target five genes at once compared to trying to insert cDNA for five different genes,” says Dr. Ahituv. The team is exploring various gene upregulation methods—cDNA insertion, zinc fingers, TALENs—to determine which proves safest and most effective for clinical applications.

Toward Clinical Applications

Moving from mice to humans presents challenges, but the foundation is promising. The procedure builds on established medical techniques: liposuction to extract fat cells, laboratory modification, and reimplantation using plastic surgery methods.

Critical safety features include:

- Using patients’ own cells to prevent immune rejection, with potential to engineer these cells to secrete factors that recruit immune cells to the tumor site or enhance anti-cancer immune activity

- The terminal differentiation status of fat cells, meaning they don’t divide after implantation

- Reversible systems through two distinct mechanisms:

- A drug that allows for temporal control of the treatment

- Implantable and removable cell scaffolds

Long-term viability is another advantage of adipocytes. In the team’s obesity research, modified fat cells maintained their effectiveness in mice for nearly a year. “These mice continued to resist weight gain on high-fat diets throughout this extended period,” notes Dr. Ahituv, “suggesting the engineered cells remain functional long-term.”

For personalized treatments, the team collaborates with Dr. Jennifer Rosenbluth at UCSF, who maintains a biobank of over 2,000 breast cancer specimens. This allows them to test patient-specific approaches and optimize treatments for different cancer subtypes, including HER2-positive tumors and those with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations. They’re investigating how specific molecular subtypes rely on particular metabolic pathways, allowing targeted customization of their approach.

Beyond Cancer: A Platform Technology

The versatility of engineered fat cells extends well beyond cancer treatment. “For diabetes, we envision cells that sense glucose levels and respond by secreting insulin,” says Dr. Ahituv. “For conditions like hemochromatosis, they could act as ‘cleanup systems’, absorbing excess iron from the bloodstream.”

By publishing their research, the team hopes to catalyze adoption across multiple disciplines. “As a single research team, we can’t explore all potential applications ourselves,” Dr. Ahituv acknowledges. “We hope other laboratories and industry partners will begin working with these engineered cells for various therapeutic approaches.”

In the broader landscape of precision medicine, these adaptable cellular platforms align perfectly with personalized therapeutic strategies—offering highly targeted interventions with potentially fewer side effects than conventional therapies.

Future Horizons

Dr. Ahituv maintains a cautious optimism about the future of this research. While specific plans remain flexible, the team aims to continue exploring the potential of engineered fat cells in treating a variety of cancers, with a particular focus on those in difficult-to-access locations.

He hopes this research inspires others to embrace authenticity and embark on their own journeys of discovery. “Sharing is essential,” he emphasizes. “Together, we are stronger.”

A Scientific Legacy

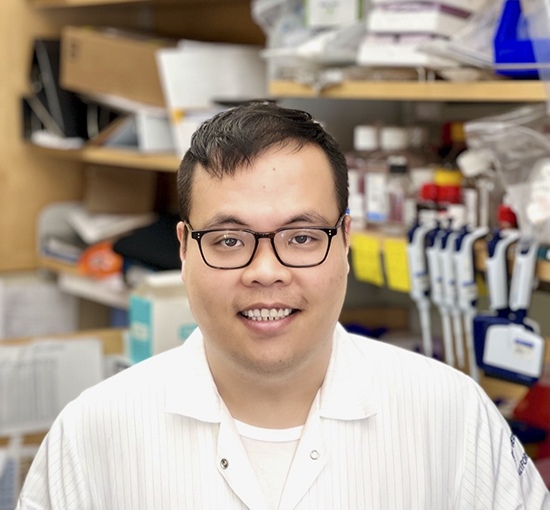

The publication of this research in Nature Biotechnology carries profound personal meaning for the team. The first author, Dr. Hai Nguyen, joined Dr. Ahituv’s lab from Berkeley, bringing expertise in adipose tissue biology that was instrumental to the project.

“He was an amazing scientist,” Dr. Ahituv recalls. “He secured a faculty position at UT Austin after just three years—remarkably quick in our field.”

Tragically, Dr. Nguyen suffered a major stroke in October 2024 at age 35 and passed away two weeks later. Completing this publication became a deeply personal mission for Dr. Ahituv—a way to honor his colleague’s contributions and memory.

In recognition of Dr. Nguyen’s scientific promise, UT Austin has established an annual seminar series and fellowship in his name, along with a commemorative tree on campus.

This research stands as part of Dr. Nguyen’s scientific legacy—work that may ultimately help countless patients while serving as a testament to a brilliant career cut tragically short.