The Odyssey of Ekgmowechashala: Unearthing a Primal Puzzle

In an enthralling new study featured in the Journal of Human Evolution, a team of scientists from the University of Kansas and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing has shed light on a remarkable primate named Ekgmowechashala. This ancient primate, which roamed North America around 30 million years ago, represents the last of its kind before the arrival of Homo sapiens on the continent. The period in which it lived was marked by significant climatic upheaval, portraying Ekgmowechashala as a solitary survivor in an evolving world. The discovery of a new primate closely related to Ekgmowechashala, unearthed in China, has provided unprecedented insights into Ekgmowechashala’s, origin, existence, and migratory patterns. Kathleen Rust, a doctoral candidate spearheading this research, has made significant strides in decoding the primate’s unique dental morphology, thereby unraveling its unexpected Asian origins and firmly establishing its place in evolutionary history.

The name ‘Ekgmowechashala,’ stemming from the Sioux language and meaning ‘Little Cat Man,’ reflects the primate’s discovery in South Dakota and the absence of a Sioux term for “monkey.” This intriguing nomenclature is deeply rooted in Native American heritage. Kathleen Rust’s fascination with early primate evolution, which began after the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, found a perfect research ground at the University of Kansas. Here, previously undescribed Ekgmowechashala fossils, alongside specimens from China, awaited examination, setting the stage for groundbreaking discoveries about the impacts of environmental shifts on these ancient beings.

Ekgmowechashala’s emergence post-dinosaur extinction highlights a pivotal period in primate history. With dinosaurs no longer dominating the landscapes, mammals, including primates, began to flourish and diversify. This era also coincided with a significant rise in global temperatures, peaking during the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum. This climatic change enabled species from warmer regions near the equator to migrate to higher latitudes, facilitating the spread of various mammals, primarily from Asia, into North America. This migration marked the beginning of primates in North America during the Eocene epoch.

From approximately 55 to 35 million years ago, North America’s landscape was unrecognizable compared to today, resembling lush subtropical rainforests that provided a nurturing habitat for primates. However, the climate eventually shifted dramatically towards the end of the Eocene (around 34 million years ago), characterized by a sudden cooling and drying period. This drastic environmental change resulted in the extinction of all primates across North America and Europe. Approximately 4 million years later, the fossil record revealed the unexpected presence of Ekgmowechashala, sparking curiosity about its origin and adaptability.

Contrary to initial beliefs, research suggests that Ekgmowechashala likely evolved in Asia before migrating to North America. This hypothesis is supported by the discovery of two species of Ekgmowechashala in areas such as Nebraska, South Dakota, and Oregon, highlighting the primate’s remarkable adaptability and resilience in new and challenging environments.

In terms of classification, Ekgmowechashala belongs to one of the earliest groups of true primates observed in the fossil record, resembling lemur-like primates in their anatomy. These primates display characteristics that set them apart from other mammals, underscoring their unique evolutionary position. Although their precise relation to modern monkeys and lemurs is debated, the general consensus leans towards a lemur-like anatomy.

The discovery of Ekgmowechashala in the fossil record, long after the extinction of its primate relatives in North America, presents an intriguing evolutionary puzzle. This unexpected appearance during a period of significant environmental change underscores the primate’s adaptability and resilience. The research sheds light on the primate’s evolution in Asia before its migration to North America, emphasizing its ability to thrive in harsh conditions.

Ekgmowechashala’s rediscovery exemplifies the Lazarus effect in paleontology, demonstrating the enduring resilience of species against environmental challenges. Its journey across time and continents offers critical insights into the adaptation of species in response to climatic changes, mirroring the current challenges faced by biodiversity amidst human-induced climate change. Today’s species, unlike Ekgmowechashala, must navigate a world heavily altered by human activities, highlighting the urgency of conservation efforts.

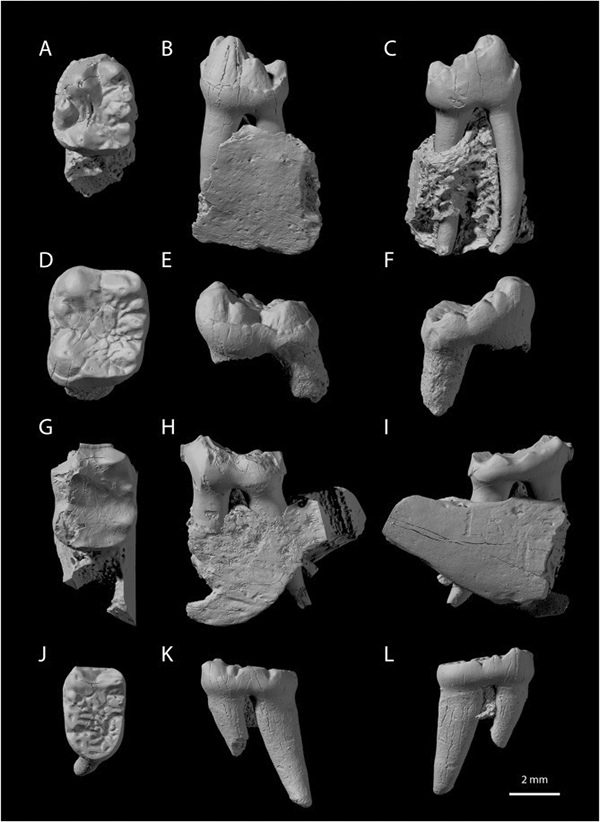

The study of Ekgmowechashala heavily relied on morphological analysis, particularly vital when DNA is unavailable, as is the case with fossils. This analysis, focused on the preserved physical features such as morphology and anatomy, was predominantly based on the primate’s dental structures. By examining every detail of the teeth, scientists could draw conclusions about the species’ evolutionary relationships and diet. The unique dental morphology of Ekgmowechashala, distinct from other known species, was crucial in establishing its classification and understanding its dietary habits. The study of its teeth, characterized by a bulbous and puffy appearance with wrinkled enamel, suggests a diet adapted to hard food items, aligning with the environmental conditions of global cooling and drying during its time.

The unexpected emergence of Ekgmowechashala in the North American fossil record, millions of years after the extinction of other primates on the continent, presents a significant and surprising discovery. This finding raises fascinating questions about primate evolution and migration, especially considering the absence of any close relatives of Ekgmowechashala in North America and the need to turn to Asia to find its nearest kin.

Rust’s study names a new fossil primate species from China called Paleohodites from China, which is the closest relative to Ekgmowechashala, and thus helps to elucidate the Asian origin of Ekgmowechashala. The journey of Ekgmowechashala across Beringia, the land bridge connecting Asia and North America, is a testament to its survival in the face of severe cooling and drying conditions. Despite its relatively brief existence compared to other extinct primates, Ekgmowechashala’s tenure outlasts that of humans, who have been present for only about 150,000 years.

In summary, the story of Ekgmowechashala is not just about a species but a narrative that spans millions of years, reflecting resilience, adaptation, and the intricate interplay between life and changing environments. As we delve deeper into our planet’s past, we gain invaluable insights that resonate with our current challenges, reminding us of our integral role in this vast web of existence.