The Ornate Woven Landscape by Taiwanese Artist, Lee Chen-Lin

“Chirp, chirp, and chirp” – the lyrics in the opening of the folk song, “Mulan Poem”, dating back to the Northern Dynasties (386 — 581 AD) – vividly describe the sound of weaving. It illustrates the busy life of women in ancient China weaving cloth with their feet tapping on the pedals of wooden looms; a weaving method used for centuries.

Then, in the early 19th century, a French weaver and merchant, Joseph Marie Jacquard, designed the first programmable loom in human history, the Jacquard Loom. He developed a system of punch cards to control the weaving patterns on the loom. This mechanical weaving technique was later refined into paper-roll piano recordings and inspired IBM founder Herman Hollerith to use punch cards to record data and do computer programming. In honor of the textile industry, IBM later named its operating system OS/2 Warp in 1994 (warp is the warp on textile cloth). (Data source: Baidu)

Digitized Jacquard machines have not only elevated weaving and mass production but have also found their way to the arts. Taiwanese artist Lee Chen-Lin uses the digitalized Jacquard machine to weave her own artistic and one-of-the-kind tapestries. In the interlacing of warp and weft, she applies her sensitivity to the logic of abstract coding and color texture in weaving. Her unique designs demonstrate her superb artistic perception and weaving skills. Hence she has built a name for herself as a talented weaving artist. Currently, there are only a handful of artists like her in Taiwan.

When Lee Chen-Lin was a graduate student at the Tainan National University of the Arts, she buried her head in the weaving process and used the school’s Jacquard machine to weave her first exhibition series, “Variation of Landscape”, in memory of her childhood hometown, Hualien. But it was a memory that she didn’t want to touch for a long time. Because of the harsh living environment in her childhood, she had many painful memories. “Looking at the mountains is not a mountain” described her interpretation of the natural environment of Hualien at that time. However, during her two years in graduate school, she resisted the reluctance in her heart and faced the past with heightened perseverance. This creative period also became her healing process. Slowly, through weaving, she learned to let go of the past.

After graduating, Lee Chen-Lin did not join the commercial weaving industry as expected. Instead, she chose to become a weaving artist. The first challenge she faced was to acquire a digital Jacquard machine, which was quite expensive by itself, not to mention the coding that came with it. Later, with the help of her instructor at graduate school, she was fortunate to obtain a second-hand Jacquard machine. In lieu of the expensive “software”, she used Photoshop to draw the patterns to assist her weaving.

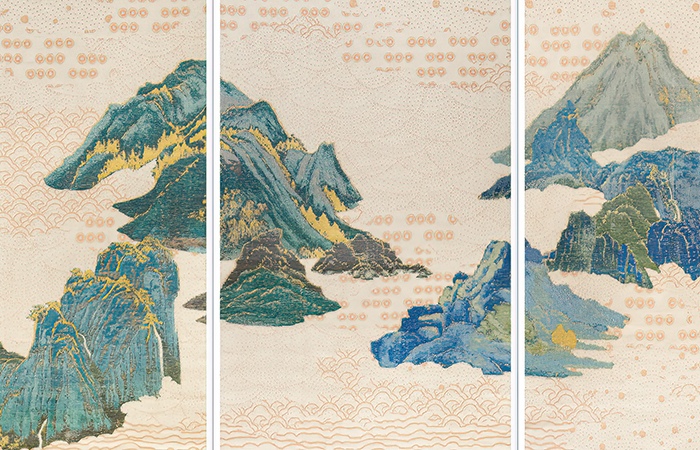

Upon solving many problems, Lee Chen-Lin began to devote herself to artistic creation. At the same time, she developed a new take on weaving – to reverse the traditional concept of treating tapestry as a continuation of the painting. According to Lee Chen-Lin, “regardless of the relationship between tapestries and paintings in the West, we can also know from the collection at the Palace Museum that Kesi reflects the characteristics of calligraphy and painting and weaving techniques of the times. Overall, the beauty of visual effects created by weaving is very similar to that of paintings in that the fabric is regarded as the communication medium of painting, and it exists to serve painting.”

In order to find “new possibilities”, Lee Chen-Lin began to study landscapes. In addition, she went to Suzhou to visit the classical Chinese landscape gardens. From these experiences, she learned about the ingenuity of the ancient Chinese when designing spaces. The natural landscape is reproduced so vividly that she wrote with recognition: “The inner wall of the garden not only defines the boundary but penetrates and shields the double symbolic nature of inside and outside. By means of natural to artificial space, it has become my attempt to create another intermediary space leading to other worlds or a ritual of how my heart observes the external world.”

Lee Chen-Lin then re-examined the natural beauty of Hualien. This time, her state of mind was like the “mountains are once again mountains” stage. The rediscovery of the beauty of her hometown drove her to create the “Borrowed Scenery” series. She “uses the Chinese gardening method to refer to the ‘landscape’ of Hualien’s hometown, not fragmentation, but a narrative relationship. Through overt or dark hints, it creates order from many unrelated elements and achieves an understanding of virtual or real, the process of conflict between landscapes.”

And her piece, “Sea Rice Fields” expresses her state of mind even more closely. The inspiration came from the lyrics “How can you know the beauty of spring if you don’t enter into a garden”, as Du Liniang lamented in The Peony Pavilion when stepping into the garden from her boudoir. The “Borrowed Scenery” symbolizes the awakening into free life after letting go of the past.

Afterward, Lee Chen-Lin went to Kyoto, Japan, to visit the gardens. There she observed that: “the monks raked out repeated textures in the white sand of the garden in order to understand Zen Buddhism, and carved traces of repetition and order in the blank space of the original Chinese landscape styles – these familiar patterns are the record of human life experience and history. It is an important carrier of civilization, expressing simple aesthetic awareness and a special language for spiritual beliefs.”

Therefore, a series “using Shanshui as the function and simple landscapes as the body” was developed by Lee Chen-Lin.

Lee Chen-Lin’s “Fu Shou Stone” series reflects her keen observation and creativity, a manifestation of a bizarre phenomenon she witnessed while growing up: “I still remember what I saw in my childhood. The pink stuff near the pond beside the ditch turned out to be the hope of the people in the 1980s that Fushou snails could make a fortune, without knowing it caused harm to the ecological environment of Taiwan. The famous image of Monet’s water lily and the shape of pebbles were used in this series to suggest the theme – the existence of reclaimed water. In order to convey the change in water quality, she clothed the deconstructed hardware accessories and assembled them into the image of artificial coral, along with dry plants and naturally dead insects immersed in chemical agents for several months, randomly mutated to grow into familiar and unfamiliar forms. She then wrapped them in a shiny gold coat and filled the gaps with sparkling, bright, and ubiquitous glass eggs, one by one, by painting with a brush… With jewelry elements, such as pearls and artificial diamonds, it deliberately made the vocabulary of the material itself by spreading out a gorgeous, absurd, and beautiful but alarming pool scene.”

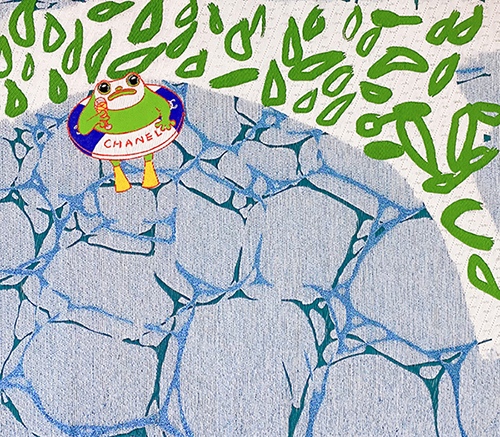

During the covid epidemic and because of the isolation in lockdown, Lee Chen-Lin adopted a simple and humorous mood to face serious issues. She designed “her first anthropomorphic graphic character – a Taiwan frog named fāfā.” At the same time, because her digital Jacquard machine was almost completely damaged, she had to find new ways to realize her Taiwan frog fāfā creation. So she searched for manufacturers to help her weave. As it turned out, most factories lacked interest in producing a single piece of hers because they prefer to maintain economic production capacity with large orders. Finally, after a lot of hard work, she found a factory willing to help with the weaving and completed her “That Greenpond” series. This process also helped her achieve her original intention of “testing more delicately woven textiles in a slow and precise way”. Different from traditional manufacturers, they mainly focus on fast and mass production, which results in a lot of unnecessary waste according to Lee Chen-Lin.

Lee Chen-Lin’s woven tapestries reflect a thoughtful and creative artist who is not afraid of challenges, has the courage to innovate, and carefully composes unique works of art. We hope that she is not only able to purchase a new digital Jacquard machine to continue her creative career but also to lead the textile industry in new production directions.

Lee Chen-Lin’s Bio