The Picasso of Snails: Art in Nature's Smallest Forms

In the misty limestone karsts of Southeast Asia, an extraordinary discovery has emerged: a tiny architect with a flair for the avant-garde. Meet Anauchen picasso, a 3-millimeter snail whose shell defies conventional design with its sharply angular, rectangular whorls reminiscent of the great cubist master’s revolutionary art. Discovered by an international team of malacologists led by Serbian PhD student Vukašin Gojšina and Hungarian advisor Barna Páll-Gergely, this diminutive creature represents not just a new species, but a testament to nature’s endless capacity for creativity and surprise. Their research was published in April 2025, ZooKeys.

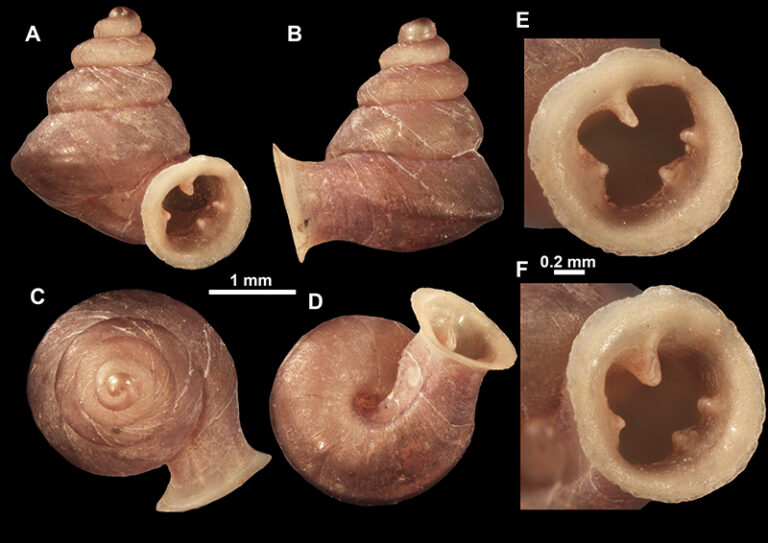

Beyond its artistic shell, Anauchen picasso belongs to a fascinating collection of microsnails whose complexity belies their small stature. These tiny mollusks, all measuring less than 5mm, feature intricate defense systems with tooth-like barriers at their apertures to ward off predators. Some species have evolved to carry their shells in unconventional orientations: upside-down or with apertures that turn dramatically upward or downward. Such adaptations highlight the remarkable diversity found within these understudied ecosystems, where evolution has crafted solutions as unique as they are beautiful.

The discovery of these 46 new snail species across Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam comes with a bittersweet note. Several specimens were found in museum collections dating back to the 1980s, representing habitats that may no longer exist. The limestone landscapes that these specialized creatures call home are rapidly disappearing to deforestation and quarrying, threatening countless undiscovered species. To understand more about this remarkable discovery and the passion driving such research, we spoke directly with Vukašin Gojšina. The details are revealed in the following.

Can you share a bit about your educational journey and what drew you to the study of malacology and microsnails in particular?

I finished my bachelor and master studies at the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, where I am also currently employed and on a PhD. My love for snails was totally spontaneous. When I was in the second year of my studies, I just realized that I wanted to study snails, and that was it! Microsnails, of course, specifically drew my attention because I saw them as a minute art of nature. I was always fascinated by how beautiful snails can be, and this is even better when you realize that they can be so small! And of course, Southeast Asia is home to some of the most beautiful snails in the world!

What was your first reaction upon encountering Anauchen picasso, and what led you to connect its shell design to the artistic language of Cubism?

The first time I saw this species under the stereomicroscope, my first impression was, of course, its unique shell morphology, which undoubtedly led me to the conclusion that it is a new species! The connection to Cubism was due to the fact that it really looks like a cubist interpretation of Anauchen species with rounded whorls, due to the presence of a strong keel on the last whorl which makes it look angled!

In what ways does studying such tiny, often overlooked creatures like microsnails reshape our understanding of biodiversity in regions like Southeast Asia?

The discovery of a large number of new species in Southeast Asia certainly emphasizes its rich biodiversity! It also shows that probably a lot more is yet to be discovered, and such a high level of endemism further emphasizes the importance of protection of the habitats not just for snails, but in general.

Several of the species you described were identified from museum specimens collected decades ago. What does this say about the role of historical collections in modern biodiversity research?

Historical collections stored in museums are especially important for research. These collections very frequently contain quite a lot of yet undescribed species. We described several species this way but also received extensive material of already described species which was very important for filling distribution gaps and understanding intraspecific variability.

Many of the habitats where these snails were originally found have since been destroyed. How do you navigate the emotional and scientific challenges of documenting species that may already be extinct in the wild?

It is not easy, of course. We are currently in a sixth mass extinction, and it seems necessary to give our best to describe as much as we can in hope that these species will be known and protected. So we feel sadness when we see that such beautiful creatures are so vulnerable, but we feel good giving our best to save them – to put the spotlight on them! After all, as biologists, this is our duty.

Your research mentions complex shell structures, such as tooth-like barriers and inverted apertures. What evolutionary pressures might be shaping such extreme morphological adaptations in these microsnails?

These traits certainly help these snails to protect themselves from numerous predators. Some of these snails even have claw-like barriers with hooked ends pointing outside the aperture, which is probably a result of rapid adaptive evolution and serves to additionally protect against predators. There was a study which confirmed that if these claw-like teeth were broken, the snail was far less successful against the predator, and if the detached part of the aperture is also broken/removed, the survival rate becomes very low.

What does the discovery of 46 new species in a single study suggest about the hidden richness of life in Southeast Asia’s limestone ecosystems—and how much might still be undiscovered?

It certainly justifies the title of Southeast Asia as one of the biodiversity hotspots. This paper described 46 new species from the family Hypselostomatidae, but in 2023, several authors of this paper described 42 species from a single genus, again in Hypselostomatidae. This means 88 new species in just two papers, which is really incredible. It truly tells us a lot about the diversity in this region but also that there are a lot more new species to be discovered. Hypselostomatidae is a large family with 13 genera included, and if these revisions continue, there is no doubt that the number of species will significantly increase!

How can taxonomic work like yours inform conservation strategies, especially for organisms that are hyper-local and highly sensitive to environmental change?

I would say that this is more or less straightforward. We have examined quite a number of specimens across Southeast Asia, and still, it is true that many species are local endemics, restricted rock-dwellers. We have made this quite clear in our work, and we even noted which species are probably highly endangered by quarry work or their type localities are even destroyed. If one species is restricted to one small limestone hill, the obvious strategy is not to disturb it by quarry work. This way, the species will be saved.

In naming the snail after Picasso, you’ve bridged scientific observation and artistic metaphor. How important is it for scientists to engage with culture and storytelling when communicating discoveries?

It probably becomes more and more important when it comes to, for example, conservation. By naming a species after a famous person, you not only just honored that person, you also put a spotlight on the species; the species becomes “more important” and definitely more visible to other people. Who knows, maybe this will help with the protection of the habitat of this species! I think that when a species is named after you, you become eternal. Pablo Picasso is already eternal, but why not enhance his eternity a bit with a new snail?

Given the increasing rate of habitat loss due to deforestation and quarrying, what actions would you most like to see from governments or global institutions to protect these fragile ecosystems?

Many of these microsnails are local endemics, restricted to limestone habitats, and most of them are known just from a single limestone hill or several hills in the region. Quarrying and destroying these hills, of course, means destroying the only habitat of these snails and leads to the extinction of the species. The only reasonable action would be to cease the quarrying or at least prevent destroying whole limestone hills. The quarrying not only leads to an unpleasant, post-apocalyptic view but also to a huge biodiversity loss.

Lastly, what do these minute and intricate creatures teach us, not just about evolution and ecology, but about how we choose to see and value life on Earth?

The way I see it, they teach us how beautiful nature can be, even when it comes to these microsnails which are overlooked by the vast majority of the population. They should teach us how to respect Earth and its biodiversity, how to find joy and art in it, how to protect endangered species, and how to respect their habitats. They should teach us that we are not the only species inhabiting this planet, not even the most beautiful one!

Conclusion

As we delve deeper into the hidden corners of our planet, discoveries like Anauchen picasso remind us that art and science are not separate domains but rather complementary lenses through which we can appreciate the world. These tiny snails, with their cubist shells and remarkable adaptations, challenge our perception of what nature can create. Yet their discovery also serves as a crucial warning—each limestone outcrop destroyed may take with it dozens of unique species before they’re ever documented. The race to catalog this biodiversity isn’t merely academic; it’s an urgent effort to record these evolutionary masterpieces before they vanish forever. Through the dedicated work of researchers like Gojšina and his team, we glimpse both the wonder of natural design and our profound responsibility to preserve it for future generations.